Article

| Is ‘hate crime’ a relevant and useful way of conceptualising some forms of school bullying ? by Nathan Hall Carol Hayden ICJS, Institute for criminal justice studies, University of Portsmouth, England Theme : International Journal on Violence and School, n°3, April 2007 |

| The article sets out to explore whether the concept of ‘hate crime’ is a relevant and useful way to conceptualise some forms of school bullying between children. We argue that the concept of hate crime can be readily and usefully applied to some bullying behaviours in schools, but should be done so with caution. In particular, viewing some forms of bullying as hate crime may give new impetus to intervention strategies for those involved in the most serious situations. English text. |

Keywords : hate crime, bullying.

| PDF file here. Background

In Britain, the report of the Steer committee (the practitioners group on school discipline and behaviour) as well as ‘Every Child Matters’ (DfES, 2004) gives new impetus to thinking about how we create safer environments for children. ‘Every Child Matters’ is a programme of change for children and young people that aims to enhance the way in which professionals work together to provide children's care. It promotes the development of multi-disciplinary teams co-located around schools, which sets a context for professionals to address problem behaviour that crosses the home, school and community environments. The obligation to intervene to address bullying and create safer environments can be made on the basis of the vulnerability of children as victims, as well as their basic right to feel safe at school, as a pre-requisite to healthy development and achievement. It is also worth remembering that children (in comparison with adults) have less choice or control over where they go to school and with whom they have to spend their time – in a classroom, or sharing a desk and so on. Although it is well recognised that bullying behaviour can happen anywhere, the particular circumstances of the school, as well as adult responsibilities towards children in this setting has tended to provide the strongest focus for research on children. Indeed, Cawson, Wattam, Brooker, and Kelly (2000) have argued that the term bullying is often seen as intrinsic to the school setting, rather than as a description of the behaviours themselves. We have known for some time that bullying effects a large minority of school children; experts indicate that between 10-20% of school children report being bullied over a three to six month period and a minority of victims suffer long-term victimisation (Smith, Talamelli, Cowie, Naylor and Chauhan, 2004). A great deal of effort has been expended on trying to reduce the problem and research reviews of the effectiveness of interventions are underway (Blaya, Debarbieux, Rubi and Moignard, 2005; ABA, 2006). However, bullying is only one of a number of safety, victimisation and behaviour management issues faced by schools and young people in their daily lives. To complicate matters further evidence suggests an inter-connection or overlap between bullying, non-attendance, school exclusion, anti-social and offending behaviour (Bowles, Reyes and Pradiptyo, 2005). Perpetrators of very aggressive behaviour are often victims of abusive behaviour themselves and not only within the school setting (Boswell, 1995). An additional concern of this article is the extent to which some victimisations are a criminal offence. Some victimisations in school are based on prejudiced and discriminatory behaviour and are of crucial importance in the current political climate in Britain, and elsewhere in the world – particularly in relation to population migration and concerns about increasing Islamophobia. Cases of wounding as well as the fatal stabbing of pupils on and around school sites in Britain in recent years, have led to proposals for additional powers for teachers to stop and search and for airport style scanners to be available to schools (Elliot and Goodchild, 2006). In this context the inter-connection between school and community safety issues has become high profile and adds to the need to question whether some of the specific actions and circumstances involving school pupils should be seen as ‘hate crimes’ rather than bullying behaviour. What we propose here is to look at the additional insights that may be offered on the issue, if we compare what is known about bullying, with what is known about hate crime. An additional impetus to this analysis is the fact that the police already take an operational approach in ‘Safer Schools Partnerships’ (SSPs) in Britain. SSPs are a joint initiative between the Department for Education and Skills (DfES), the Youth Justice Board (YJB) and Association of Chief Police Officers (ACPO). They are part of a number of measures that link behaviour in and around schools to an explicit crime prevention programme. Pilot partnerships began in 2002 and were located in areas with high levels of street crime, or crime ‘hotspots.’ In these early partnerships a number of models operated, including a dedicated full-time police officer based in a secondary school and a ‘lighter touch’ model in which police officers are part of multi-agency partnerships attached to a cluster of schools. Key objectives of SSPs include reducing victimisation, criminality and anti-social behaviour within and around the school; identifying and working with those at risk of being victims or offenders; and, creating a safer environment in which children can learn (Bowles et al, 2005). The evaluation team for SSPs conclude that ‘there are clear signs that pupils in SSP intervention schools, particularly YJB/ACPO schools [which had more resources], feel significantly safer than their counterparts in comparison schools’ (Bowles et al, 2005, p.11). However, there were problems with clarity about professional roles and some teachers were wary about the idea of a police officer on the school site. As of 2006 the approach is being mainstreamed across schools in England and Wales, as part of the ‘Every Child Matters’ and ‘Respect’ agendas (DfES, 2006). These changes could also be seen as part of what has been referred to as the ‘criminalisation of social policy’ (Hayden, 2005). In developing our argument we were influenced by Furniss (2000) in her seminal article -‘bullying – it’s not a crime, is it?’. She concludes that sometimes bullying is a crime and that children should be afforded the same protection as adults. In particular, she argues that intervention from the criminal justice system is appropriate in relation to incidents that are too serious to be dealt with by the school alone and in cases where the school is ineffective in tackling the bullies and protecting victims. Indeed, some commentators in the United States are critical of their more recent (in comparison with Europe) adoption of the term bullying, arguing that anti-bullying legislation may serve to undermine existing legal rights, drawing discussion away from a civil rights framework towards one that focuses on individual behaviour (Stein, 2003, 787). Recognition of the responsibility of the education service in Britain now extends to paying compensation for bullying endured whilst in school when the school has been alerted to the bullying and fails to prevent it (Taylor, 2006). Amongst the observations of the Steer committee is the way that parents are increasingly likely to involve lawyers in disputes about their children’s behaviour; a situation in which teachers and schools may in turn respond with the use of more emotive and sometimes legalistic language. Many of the disputes over pupil exclusions and reinstatements have involved the conflicting rights of children to an education based in school, the rights of other children to learn in a conducive environment and the rights of teachers to teach in an environment free of abusive and stressful behaviour. The latter issue has led to teaching unions supporting teachers in their refusal to teach individual pupils on health and safety grounds (NAS/UWT, 2003) and teachers receiving compensation for injuries sustained from pupils (Smithers, 2005). In other words the rights and compensation agenda has already entered schools in Britain. Lawyers defend the rights of individual pupils to be reinstated in a school that has excluded them because of their behaviour; whilst on the other hand calling for the exclusion of pupils who bully others. Uncertainties about the legality of what teachers can do in order to manage pupil behaviour has led Rod Morgan (Chair of the Youth Justice Board) to comment that too many children are appearing before the courts because teachers and care home workers are afraid and uncertain about how to respond to children’s behaviour. Morgan advocates restorative justice schemes and more police officers in schools with the most difficult behaviour, with a focus on dealing with problems in situ, rather than passing them on to the courts (Stewart, 2006). Historically, teachers in Britain rarely see bullying as a matter that should involve the police and prosecutions are rare (Furniss, 2000). Yet it is clear that some incidents of bullying involve actions that are a criminal offence – theft, extortion, physical assault, racial and sexual harassment and so on. Given the evidence about the scale of bullying in schools it is clear that adopting a perspective that focuses on whether some forms of bullying should be treated primarily as a criminal offence could have worrying consequences in terms of the potential for ‘net-widening’ – or the drawing in to the criminal justice system of people who would previously be dealt with outside it. On the other hand it could be argued (as Furniss, 2000, does) that the seriousness of some bullying means that we should take stronger action against the perpetrators. In putting forward the concept of hate crime in relation to some forms of bullying behaviour we want to try and look constructively at how such behaviour may be dealt with proportionately and, most importantly, with child welfare in mind. It is important to emphasise at the outset that most good quality research evidence, as well as reviews and enquiries like that conducted by the Steer committee in Britain, conclude that for most of the time schools are orderly places and that it is low-level disruptive behaviour that is the everyday issue for teachers. The focus on ‘disruptive’ behaviour is however, very teacher-centred. Surveys of young people reveal a different picture and a range of victimisations on the school site. For example, although a national sample of secondary school pupils found that most (76%) children reported feeling ‘fairly safe’ or ‘very safe’ at school; 15% reported feeling ‘fairly unsafe’ or ‘very unsafe’ (MORI, 2004). Those who felt ‘very unsafe’ made up 3% of the sample, or 30 children in every 1,000 pupils. Whether young people feel safe in school is likely to be influenced by a number of things, including personal experience of victimisation and witnessing the victimisation of others. However, the media can also be influential. Visser (2006) in the first edition of this journal highlighted the role of the media in sensationalizing particular cases and contributing to a widespread perception that things are getting worse. Arguably bullying has become part of the arena in which individual cases, whether celebrities or very severe cases of harm to contemporary pupils, become emblematic of unwanted behaviour in schools. Whether conceptualising some of these unwanted behaviours as ‘hate crime’ is relevant and useful is an issue that we will consider as we conclude this article. Suffice to say here, we acknowledge that hate crime is also an emotive concept with connotations that may lead to actions in some schools that are exclusionary, punitive and criminalising, unless professionals have a clear philosophy about reducing harm. Research on bullying in schools is well established in Britain and many other countries worldwide (Smith, 2002a). Bullying is also an everyday term in the English language, frequently used to describe aggressive behaviour that is not repeated. Yet the issue of repetition over time is crucial in the academic definition of bullying, in comparison with other forms of aggressive behaviour which are not repeated. According to one of the leading academic experts on bullying: ‘bullying can be seen as a form of aggressive behaviour that is deliberately hurtful, repeated over time and typically happens in situations where it is difficult for a victim to defend themselves’ (Smith, 2002b,117) and as ‘a systematic abuse of power’ (Smith and Sharp, 1994, quoted in Smith, 2002b,117). Smith (2002a, 120-121) has highlighted children with a disability as well as racist and homophobic bullying within the arguments about children at risk of bullying. Interestingly the language used in relation to these groups: children with behavioural problems may be ‘provocative victims’ and ‘teasing’ is problematic in some ways; the former idea could also be seen as victim-blaming, the second could be seen as downplaying the importance of racist behaviour. The concept of hate crime is more recent than that of bullying and better established in the United States, than Europe. In the United States, hate crime legislation identifies offences motivated by animosity to certain groups of people as deserving of higher penalties than crimes not motivated in this way (Gadd, 2003). Interest in the concept has steadily grown in Britain since the publication of Sir William Macpherson’s inquiry into the racist murder of the black teenager Stephen Lawrence in London in 1993 (Macpherson, 1999). Specific legislation also exists outlawing offences motivated by racial and religious hatred, and offences aggravated by homophobia and disability bias. For policing purposes in England, Wales and Northern Ireland, hate crime is defined as ‘any incident, which may or may not constitute a criminal offence, which is perceived by the victim or any other person, as being motivated by prejudice or hate’ (ACPO, 2005, 9). Emerging research on hate crime is beginning to produce profiles of victim, offender and offence characteristics, each of which share a number of interesting and significant parallels with what is known about bullying in schools (see Table 3, later in this article). Within safer schools partnerships and elsewhere in the education service some of the language more commonly used in the criminal justice system has already entered schools in relation to pupil behaviour. For example, combating ‘hate crime’ is used to cover equal opportunities issues, as well as in relation to broader work on police and community relations and within attempts to make schools safer places (Thorpe, 2006). However, it is also clear that there is some debate and difference of opinion about how (and whether) to use specific criminal justice terminology in relation to children’s behaviour in school. Some police forces include bullying within their definition of hate crime (such as Tameside police), others separate the two terms. Other police forces (such as Thames Valley police) make a distinction between bullying and criminal behaviour (using terms such as ‘assault’, ‘theft’ and ‘criminal damage’ in relation to certain behaviours); they advise that the police should be called to schools to deal with these instances. The Home Office on the other hand views hate crime as a criminal offence (Home Office, 2006, para 1). Bullying and aggressive behaviour in schools Bullying and aggressive behaviour is common in schools, there are plenty of reviews of recent research in this field (see for example ABA Research and Evaluation Team for research on bullying in 2005 and Hayden, 2007, for a review of the various ways problematic behaviour in schools and elsewhere is measured and explained). We will not review this evidence here as readers of the journal will be familiar with the evidence. Suffice to say, research on school bullying is perhaps one of the best established and coherent traditions within research about the range of problematic behaviours in schools. Yet whilst there is broad agreement amongst researchers about the key elements that are seen to constitute bullying; Greene (2006) has raised concerns about the practical applicability of this. For example, he highlights the difficulty in establishing deliberate intent to hurt, or the determination of power imbalance specifically in bullying which is not face-to-face – as through mobile phones and the internet. Further he notes that children do not themselves include all of the definitional elements in their understanding of bullying; neither do adults in general or teachers in particular (Greene, 2006, 64). Violent and aggressive behaviour is generally seen as predominantly a male phenomenon. Behaviour that is often referred to as ‘challenging’ in the school context is also predominantly male: the ratios in Visser’s (2006) research on challenging behaviour indicate that boys outnumber girls at between 10 and 12 to one. School exclusion statistics show a ratio of four boys to one girl. However, research on bullying shows that a higher proportion of girls are involved, in comparison with other forms of problem behaviour. Although girls use and experience different types of bullying (Smith, 2000a). Boys are more frequently involved in physical bullying, girls’ bullying is more frequently indirect and relational. These differences have led to some highly critical comment in the United States context:

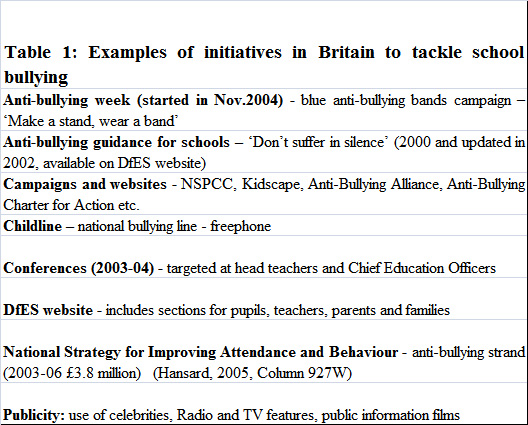

On the other hand, analysis of the backgrounds of ‘school shooters’ in the United States has found that being a victim of bullying is an important part of the background to these high profile and exceptional incidents (Verlinden, Hersen and Thomas, 2000). Leary, Kowalski, Smith and Phillips (2003, 202) note that ‘a typical school shooter feels lonely and isolated’ and that they are ‘highly sensitive to teasing and bullying.’ They conclude that some of the school shootings may have been precipitated by rejection by schoolmates or others but that three other risk factors were also common – interest in firearms or bombs, a fascination with death or Satanism and psychological problems. Whilst the spectre of school shootings may seem an extreme reference point these events, like that of suicide, warn us of the worst potential consequences of ineffective or indifferent action to tackle bullying behaviour. In the British context there is increased recognition of the potential for lethal violence in schools through weapons carrying. Estimates of weapons carrying by school age pupils in inner city areas give no grounds for complacency (see for example, CtC, 2005). Responses to bullying behaviour All schools in Britain must have a policy to prevent all forms of bullying and a wide range of initiatives and resources have been committed to combating bullying (see Table 1). School policies must set out strategies to be followed, backed up by systems to ensure effective implementation, monitoring and review. Policies must comply with the Human Rights Act 1998 and the Race Relations Act 2000. Schools are not directly responsible for bullying off their premises, but do have a common law duty of care towards their pupils (Smith, 2002b, 4). A survey of 307 schools in England and Wales, by Douglas, Warwick, Kemp, Whitty and Aggleton (1999) indicates almost universal awareness of the existence of bullying in schools, from the head teachers responding. However, this latter survey pointed to particular problems in dealing with homophobic bullying, partly because of interpretations of earlier government legislation and guidance that emphasised traditional ‘family values’ (Epstein and Johnson, 1998) and prohibited teaching that ‘advocates homosexual behaviour, which presents it as the ‘norm’, or which encourages homosexual experimentation by pupils’ (DES, 1987,197). More recently the Steer committee reported on the most problematic bullying issues for schools: ‘Schools find tackling homophobic and racist bullying a particular challenge. This includes prejudice against religious and cultural minorities – Islamophobia, anti- Semitism and negative stereotyping of Gypsy/Roma and Traveller pupils.’ (Steer, 2005, 32) There is general agreement from researchers that problematic behaviour in schools, such as bullying, has to be dealt with by a whole school approach and necessarily includes individual, classroom, school-wide and community connected work, along with the active involvement of young people as well as adults (Greene, 2006). Further, action against bullying has to be an ongoing process as aggressive and problematic behaviours cannot be eliminated. More broadly, as Visser (2006) would argue, we know that a sense of belonging and inclusiveness in a school is associated with fewer behaviour problems in this setting. American research has singled out the concept of ‘school connectedness’ as the most important school-related variable that is protective for adverse outcomes, such as substance use, violence and early sexual activity (Resnick et al, 1997). For example, one study of over 83,000 pupils found that four attributes explained a large part of between school variance in school-connectedness (McNeely et al, 2002). These attributes included: classroom management climate; school size; severity of discipline policies and rates of participation in after school activities. School connectedness was found to be lower in schools with difficult classroom management climates and where temporary exclusion was used for minor issues. Zero Tolerance policies (often using harsh punishments like exclusion from school) were associated with reports of pupils feeling less safe, than schools with more moderate policies. So we know that action against problematic behaviour in schools is likely to have wider beneficial social consequences. We also know that the quality of teaching and learning is the starting point for improving behaviour in the classroom. Teachers who treat children and young people with respect and model wanted behaviour, especially when they are confident about their role in respect of difficult behaviour, are generally better able to respond to children’s behaviour in a way that reduces harm (Hayden, 2007). Research on hate crime As a concept ‘hate crime’ was first used in the United States in the mid-1980s (Hall, 2005). As a concept it can be argued that it sends out a strong message against unwanted behaviour. Yet few hate crimes are motivated purely by hatred, despite the terminology (Jacobs and Potter, 1998; Hall, 2005). Rather, most of the offences that we now refer to as ‘hate crimes’ are primarily a product of an offender’s negative prejudice towards a disliked characteristic that the victim possesses, such as their race, sexuality, religion or indeed any other identifiable characteristic over which the victim has little or no control. Clearly the notion of prejudice is far broader than hatred, and the use of this term considerably widens the scope for categorising the physical or verbal expression of negative prejudice of any kind as a hate crime. Interestingly, Stanko (2001) has suggested that ‘hate crime’ might be more usefully conceptualised as ‘targeted violence’. The use of the word targeted is of particular interest to us. In effect, victims of ‘hate crime’ are targeted specifically because they are different, or are perceived to be different, from a majority group. This leads us to consider the scope for labelling some forms of bullying as ‘hate crimes’ because bullying necessarily involves the deliberate targeting of the victim by the perpetrator on the basis of some perceived difference. The extent of hate crime is notoriously difficult to determine (Perry, 2001; Ewing, 2006). Much like bullying it remains significantly under-reported to the authorities for a host of reasons that include fear and intimidation, fear of reprisals, and a lack of confidence in the ability of the criminal justice system to resolve the problem. In addition official statistics for ‘hate crime’ as a distinct category of offending are not collected in England and Wales. Rather, statistics on individual types of hate crime are collected, most notably those on racially and religiously motivated offences under Section 95 of the Criminal Justice Act 1991. At the time of writing, the latest of these figures indicate that in 2004/5 the 43 police forces of England and Wales recorded 57,902 racist incidents, of which 37,028 were recorded as criminal offences. In comparison, the British Crime Survey (an annual self report survey with a nationally representative sample) estimates that there were 179,000 racist incidents in the same period, illustrating the extent of under-reporting to the police (Home Office, 2006). Of the 37,028 racially motivated offences recorded by the police in 2004/5: 61% were categorised as offences of harassment; 15% criminal damage; 14% less serious wounding and 10% common assault (Home Office, 2006b). When religiously motivated hate crime is included with racially motivated hate crime, there are about 50,000 police records a year. The annual British Crime Survey (a self-report survey) finds many more such crimes – at around 260,000 (Home Office, 2006a). The Metropolitan Police alone reported 11,799 incidents of racist and religious hate crime and 1,359 incidents of homophobic hate crime in a twelve month period (Home Office, 2006a). Research into hate crime victimisation supports the notion that much hate-based offending comprises ‘low-level’ acts of harassment which on the surface may seem trivial, but that these are often repeated and systematic (a key characteristic of ‘bullying’ behaviour), and can have a disproportionate and cumulative impact (both psychologically and physically) on both the victim and the wider community to which that victim belongs (Bowling, 1999; Chahal and Julienne, 2000; McDevitt, Balboni, Garcia and Gu, 2001; FBI, 2003; Hall, 2005). As with bullying, there is ongoing academic and practitioner debate concerning explanations of hate crime. Theories include the view that hate crimes are a consequence of the scapegoating of certain groups blamed for perceived social ills (Heitmeyer, 1993); that hate crime is a product of the interplay between social and contextual factors (such as unemployment, economic hardship, competition for scarce resources, lack of/competition for community facilities) and the psychology of certain individuals who are likely to be involved in other forms of anti-social behaviour but need someone to blame for the contextual issues (Sibbitt, 1997); or that hate crime is used as a tool to assert and maintain perceived power structures in society (Perry, 2001). However, Craig (2002) has argued that no single theory can adequately explain all types of hate crime. This, she suggests, is largely because contributory factors (perpetrators’ motives, victims’ characteristics, and cultural ideologies) differ markedly for each incident. There has been an increasing amount of research into the perpetrators of hate crime in recent years. For our purposes here four are of particular interest (Sibbitt, 1997; Byers, Crider and Biggers, 1999; McDevitt, Levin and Bennett, 2002; Docking, Kielinger and Paterson, 2003). We give most attention to the work by McDevitt et al that focuses on the motivation of participants in hate crime. Research by Docking et al (2003) has examined in detail information contained within the Metropolitan Police Service’s crime records; taking a ‘snapshot’ of police records on information provided by the victim for one day (22nd March 2001) during which forty-nine cases were recorded and analysed. We focus here on the aspects that relate most to schools and children of school age. Two-thirds of incidents were perpetrated by people known to the victim. In a quarter of all cases, school children and local youths were involved. The research also revealed that almost two-thirds of racist incidents occurred at or near the victim’s home, at or near their place of work, and at or near their school. In other words racist victimisation generally occurs as victims go about their daily lives. Furthermore, more than a fifth of racist incidents occurred between 3pm and 6pm, and of these a third of suspects were under 16 years of age. This latter finding is consistent with other research concerning the age groups of hate offenders (Sibbitt, 1997). In addition, almost half of the victims were described as ‘school children’ in the crime reports (Docking et al, 2003). Research into the perpetrators of racial violence and racial harassment in London has identified links between hate-based offending and bullying behaviour at school (Sibbitt, 1997). Through detailed fieldwork in two London boroughs, Sibbitt’s research identified a number of age-related offender typologies, of which three are of particular interest here. A particularly problematic typology of offender identified relates to15-18 year olds. Typically, young people in this age band have been subject to the prejudiced views of their elders, and at school are likely to have associated with older youths with racist attitudes and engaged in other forms of anti-social behaviour, including bullying. Younger age bands had slightly different typologies. For example, 4-10 year olds often engaged in bullying which continued away from the school environment in the form of wider harassment and intimidation. This could be related to boredom, but could be positively reinforced by older family members. Research in the United States by McDevitt et al (2002) has developed a typology of hate offenders, based on the motivation behind the offence from 169 cases in Boston. Boston police case files. Using indicators nationally accepted in the United States to identify the hate element of an offence (for example, the use of language by the offender, the perpetrator’s offending history, the presence of ‘triggering’ events, the use of hate graffiti and the location of the offence), McDevitt et al concluded that hate offenders can be placed into one of four categories based on motivation: thrill, defensive, retaliatory and those with a mission (see Table 2). ‘Thrill’ was the most common motivation, accounting for two-thirds of the 169 cases analysed (66%, 111). In other words, the vast majority of hate offences were motivated by the offender’s desire for a ‘thrill’ often because they were bored or were seeking some form of ‘excitement’. This finding supports Sibbitt’s contention that many younger racist offenders commit offences out of a sense of boredom and a need for excitement in their lives. The research found that ‘thrill’ offenders deliberately selected their target because they were ‘different’ to themselves, and that many of the offences analysed in this category were underpinned by an immature desire to display power and to enhance the offender’s own feeling of self-importance at the expense of others. In a quarter of the cases analysed (25%, 43) McDevitt et al categorised the motivation as being ‘defensive’ in its nature. In these cases, the offender committed hate offences against what he or she perceived to be outsiders or intruders in an attempt to defend or protect his or her ‘territory’. In 8% (14 cases) of the sample the hate motivation identified by McDevitt, Levin and Bennett is ‘retaliation’. This is based on the finding that a hate offence is often followed by a number of subsequent hate attacks. The researchers state that retaliatory offences are not a reaction to the presence of a particular individual or group, but rather are a reaction to a particular hate offence that has already occurred, be it real or perceived. Retaliatory offenders are therefore seen as those retaliating against, or avenging, an earlier attack. Perhaps the best example of retaliatory offending can be seen in the escalation of offences committed against Muslims (or those believed to be Muslims) in both the US and Britain in the period following the terrorist attacks in the US on September 11th 2001 (NYPD, 2002; MPS, 2002), and in the UK following the London bombings on the July 7th 2005 (Dodd, 2005). The final category identified by McDevitt et al is that of the ‘mission’ offender, representing only one case in the sample. Here the offender is totally committed to his or her hate and bigotry, and views the objects of their hate as an evil that must be removed from the world. It is clear from Table 2 that the majority of hate offenders are teenagers or young adults. Also of interest is the suggestion that hate crime is often a group activity. Furthermore, hate offences often involve whatever ‘weapons’ happen to be at hand, and occur often with little or no victim-offender history. This lends support to the contention that hate crimes are impersonal and that victims are interchangeable, although we should note here the contrast with the findings of Docking et al (2003) that suggest that in many cases the victim and offender are in fact known to each other. The final points of note in Table 2 relate to the last two categories. The offender’s commitment to their hatred is a significant factor, particularly in relation to whether or not they can be deterred from their actions. Thrill offenders are not particularly committed to their prejudice, in contrast mission offenders are fully committed to their beliefs. Defensive and retaliatory offenders fall somewhere in-between the two ends of this spectrum.

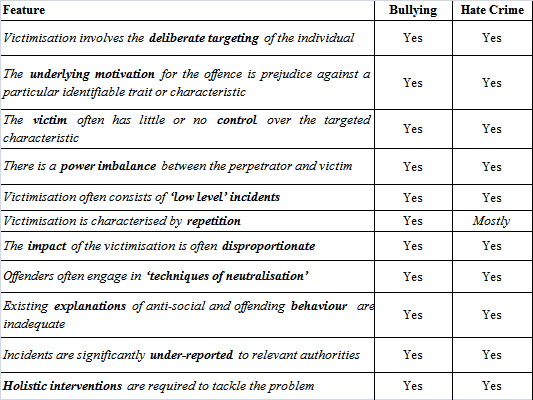

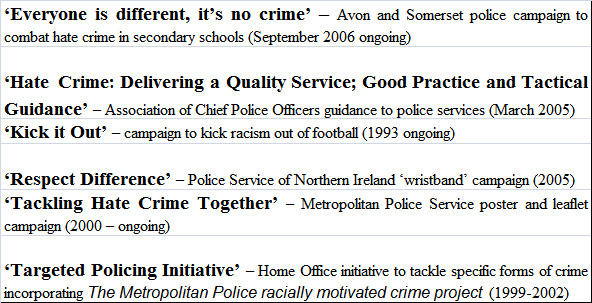

The most culpable group member is the ‘leader’, who may suggest to the group that they commit a hate offence for any of the reasons outlined above (for example, for the thrill, or to retaliate). The second category, ‘fellow travellers’ do not initiate the offence but once suggested are happy to comply with the suggestion of the leader, making them only slightly less culpable than the ‘leader’. The third identifiable category is the ‘unwilling participant’, who whilst disapproving of the situation that is occurring, still does not actively attempt to intervene in the crime, or report it to the police. For these individuals, the need for acceptance and peer group approval is the key factor in the failure to intervene. The final category is that of the ‘heroes’ who actively attempt to stop the offence from taking place. McDevitt et al suggest that this behaviour should be rewarded because their actions require immunity to social influence and a strong conscience in order to put the needs of a person they have never met before the desires of their friends or peer group. Building on this sort of idea, it is interesting to note that the UK children’s charity Childline has (at the time of writing) started a national programme that plans to actively recruit 60,000 ‘popular’ teenagers to help resolve fights between pupils, report bullying and provide support for children who have been victims (Asthana, 2006). As well as providing academics with useful information about offenders, this typology is now widely used in law enforcement in the United States and has had numerous implications in terms of policy development in this area. Finally for our purposes, research conducted in the United States by Byers et al (1999) has also revealed some interesting insights into hate crime offending by drawing on Sykes and Matza’s (1957) techniques of neutralisation, which seek to identify how perpetrators of crime justify their offending behaviour. Sykes and Matza found that offenders in general often attempted to justify their actions in a number of ways that mitigated their involvement, and that these justification techniques provided useful information about the motivation of criminals. In their study of hate crimes committed against the Amish, Byers et al found that whilst some offenders showed little or no remorse for their actions, others attempted to justify or rationalise their behaviour by using a number of ‘neutralisation techniques’. The first technique of neutralisation described by Byers et al is that of denial of injury. Here offenders attempted to neutralise their behaviour by suggesting that no real harm was done to the victim, that the offence was in effect ‘harmless fun’, and that the victim should in any case be used to being subject to certain forms of abuse, all of which combined to make the offender’s behaviour somehow acceptable. The latter is an argument akin to the view that bullying is ‘just part of growing up’. The second identified technique was that of the denial of the victim. According to Byers et al, this makes the assumption that the victim either deserved what they got, or that the victim is effectively worthless and offences against them are inconsequential either socially or legally. Essentially, then, victims are somewhat dehumanised and seen as deserving of their victimisation. The third identified technique is the appeal to higher loyalties. Here, offences may be committed through allegiance to a group. Offenders therefore may see their behaviour, and subsequently not revealing that behaviour or the behaviour of their peers, as a form of group bonding and security within their ‘in-group’. Fourthly, Byers et al suggest that some offenders will engage condemnation of the condemners. Here offenders attempt to neutralise their behaviour by questioning the right of their condemners to sit in judgement of them. This may be done by suggesting that those that condemn them are in reality no better, share similar views to the offender, and given the chance in similar circumstances would act, or may have previously acted, in a similar way to the perpetrator. The final technique relates to a denial of responsibility. Here, Byers et al explain, offenders attempts to neutralise their responsibility for their actions by claiming other factors to be the cause of their behaviour, such as, the researchers suggest, the offender’s socialisation and the way they were brought up. In other words, the blame for their behaviour lies somewhere other than with them. Furthermore, Byers et al found that many offenders broadly fitted the ‘thrill’ category described by McDevitt et al, above, and also pointed to the importance of peer support, thus highlighting the significance of shared views, and the reinforcement of those views. Offender’s attempts at justifying their actions also lend support to the view that victims are frequently dehumanised by their attackers, are viewed as subordinate to the offender, and are somehow deserving of their victimisation. This in turn reflects Perry’s (2001) notion of power, the expression of power, and the use of hate crime as a method for maintaining perceived social hierarchies and for ‘punishing’ those who attempt to disturb the social order. The insights from research on hate crime tend to suggest that whilst we are often dealing with quite common everyday circumstances and motivations in most cases, there are cases where people are highly unlikely to change their behaviour (at least in the short term) and consequently potential victims will need stronger protection from harm. Responses to hate crime As with bullying, there have been a number of national, regional and high profile initiatives that aim to raise awareness about and tackle hate crime. There is a strong emphasis on race in many of these initiatives. The project run by Avon and Somerset police (see Table 3) is an example of a wider scheme that aims to ‘educate children that committing crime because of someone’s faith, race, sexual orientation or disability is unacceptable’ (Thorpe, 2006, para 3). More broadly, the schemes aim to increase confidence in the police and to make school environments safer places. Like anti-bullying campaigns such schemes have enlisted the support of celebrities and the wristband idea is apparent in some campaigns.  Table 3: Examples of initiatives in Britain to tackle hate crime The Crime and Disorder Act 1998 created a range of new racially and religiously aggravated offences; the Criminal Justice Act 2003 introduced tougher sentences for offences motivated or aggravated by hatred of the victim’s sexual orientation or disability, and the Racial and Religious Hatred Act 2006 makes it a criminal offence ‘to use threatening words or behaviour with the intention of stirring up hatred against any group of people defined by their religious beliefs or lack of religious beliefs’ (Home Office, 2006a, para 9). Bullying and hate crime From the review of what is known about hate crime it can be argued that bullying could be seen as a form of hate crime, especially some of the more extreme cases of bullying. The connection between a background of bullying behaviour and extreme acts is not often made clearly. Much of the research on hate crime reported within this paper has focussed on race and ethnicity. However, hate crime also involves homophobic and religiously motivated behaviour. The problem of homophobic bullying in schools in Britain has again been raised following the trial of the suspects in the murder of schoolboy Damilola Taylor. On the 27th November 2000, whilst on his way home from school ten year old Damilola Taylor was stabbed in the leg with a broken glass bottle and bled to death in the stairwell of the North Peckham Estate in South East London. In August 2006, following two previous trials, brothers Danny and Rickie Preddie, who were twelve and thirteen at the time, were convicted of Damilola’s murder. However, despite the convictions, there are concerns that the role of homophobia and bullying has been somewhat overlooked throughout. Shortly after the murder, Damilola’s mother described how her son had been physically assaulted just days before he was killed, and reports suggested that Damilola had been subjected to homophobic bullying (Hari, 2006). As Hari (2006, 37) further points out; Table 4: Comparable features of bullying and hate crime Firstly, quite simply, some acts of bullying in schools will be motivated by hate and will be crimes. The concept of ‘hate crime’ may therefore help to emphasise the seriousness and law-breaking aspects of some bullying behaviour. However, we are not suggesting that all such incidents should attract the attention of the formal criminal justice system. Such a proposition would be impractical, unhelpful and unnecessary and would have the potential for criminalising behaviour that is often widespread in school environments. Nevertheless, hate crimes are committed in schools (and not all will involve bullying – some will be one-off incidents) and these need to be identified and responded to in a manner appropriate to the seriousness of the offence. We agree with Rod Morgan (of the Youth Justice Board) that in most cases, young people should be dealt with in situ and that this will need the help of the police in some cases. Secondly, conceptualising some forms of bullying behaviour as hate crime may offer new insights for understanding not just the bullying behaviour, but also the impact that this has on victims. Of course the concept has particular relevance to homophobic, racist and religiously-motivated incidents, but its use may help in differentiating levels of seriousness of both these and other types of targeted bullying behaviour. Furthermore, the typologies of hate crime offenders suggest different motivations for hate-based behaviours and different levels of likelihood of deterrence, both of which may be useful in developing interventions to address specific bullying behaviour that hitherto may not have been considered. Thirdly there is potentially considerable practical value in conceptualising some forms of bullying as hate crime as part of the work SSPs undertake, as well as in broader work on reducing crime and disorder in communities. The wider role envisaged for schools within the ‘Every Child Matters’ agenda in Britain fits well with this objective. The options for the prevention of serious bullying behaviour (as a hate crime) that subsequently become available through the pooling of resources and dissemination of ideas and information are significantly greater than schools might achieve by working alone. The partnership between the police, schools, other parts of children’s services and community organisations is important for several reasons; schools are well placed to promote ‘anti-hate’ to youth and to help in the development of positive and safer community relations. In sum we would argue that hate crime as a concept has much in common with bullying. ‘Hate crime’ as a term may serve to underline the seriousness of some bullying behaviour and emphasise that it is not behaviour that young people should ‘put up with.’ As a concept hate crime has clearer connections to unwanted and socially divisive behaviours in the community and has a stronger connection to the kind of rights agenda that underlines current thinking on the development of children’s services in Britain. Having said this we are keen to emphasise in concluding this article that the use of the concept of ‘hate crime’ also carries with it the potential for problems if used in a purely punitive way by schools. |

Bibliography

ABA, ANTI-BULLYING ALLIANCE (2005) Literature Collation on Bullying and Victimisation 2005. London: ABA Research and Evaluation Team, Unit for School and Family Studies, Goldsmiths College. See: http://www.anti-bullyingalliance.org.

ABA (2006) Anti-Bullying Alliance announces new research project, 13th March. See: http://www.ncb.org.uk/Page.asp?originx545bw_2947328094497j14y781146601.

ACPO, ASSOCIATION OF CHIEF POLICE OFFICERS (2005) Hate Crime: Delivering a Quality Service; Good Practice and Tactical Guidance. London: ACPO.

ASTHANA, A. (2006) ‘Popular’ teenagers to help fight bullying, The Observer, 18th November, 6.

BLAYA, C., DEBARBIEUX, E., RUBI, S. and MOIGNARD, B. (2005) School-based anti-bullying initiatives Crime and Justice approved title, Campbell Collaboration C2 Ripe database. See: http://www.campbellcollaboration.org.

BOSWELL, G. (1995) Violent Victims. The Prevalence of Abuse and Loss in the Lives of Section 53 Offenders. London: The Prince’s Trust.

BOWLES, R., REYES GARCIA, M., PRADIPTYO, R. (2005) Monitoring and Evaluating the Safer School Partnership Programme. London: Youth Justice Board.

BOWLING, B. (1999) Violent Racism. New York: Oxford University Press.

BYERS, B., CRIDER, B. W. and BIGGERS, G. K. (1999) Bias Crime Motivation: A Study of Hate Crime and Offender Neutralisation Techniques Used Against the Amish, Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice, 15(1), 78-96.

CAWSON, P., WATTAM, C., BROOKER, S. and KELLY, G. (2000) Child Maltreatment in the United Kingdom: a study of the prevalence of child abuse and neglect. London: NSPCC.

CHAHAL, K. and JULIENNE, L. (2000) We Can’t All Be White!: Racist Victimisation In The UK. York,:York Publishing Services Ltd.

CRAIG, K. M. (2002) Examining Hate-Motivated Aggression: A Review of the Social-Psychological Literature on Hate Crimes as a Distinct Form of Aggression. Aggression and Violent Behaviour, 7, 85-101.

CtC, COMMUNITIES THAT CARE (2005) Findings from the Safer London Youth Survey 2004. London: Communities that Care.

DES, DEPARTMENT FOR EDUCATION AND SCIENCE (1987) Circular 11/87: Sex Education at School. London: Department of Education and Science.

DfES, DEPARTMENT FOR EDUCATION AND SKILLS (2004) Every Child Matters: Change for Children in Schools. Nottingham: DfES.

DfES (2006) Safer Schools Partnerships – Mainstreaming Guidance. London: DfES.

DOCKING, M., KIELINGER, V. and PATERSON, S. (2003) Policing Racist Incidents in the Metropolitan Police Service. Paper given to the Research and Development Conference, 3rd June 2003.

DODD, V. (2005) Islamophobia blamed for attack, The Guardian, Wednesday 13th July. See: http://www.guardian.co.uk/uk_news/story/0,3604,1527288,00.html

DOUGLAS, N., WARWICK, I., KEMP, S., WHITTY, G. and AGGLETON, P. (1999) Homophobic bullying in secondary schools in England and Wales – teachers’ experiences, Health Education, 99(2), 53-60.

ELLIOTT, F. and GOODCHILD, S. (2006) Teachers to be given sweeping powers to stop and search pupils, The Independent, 5th July. See: http://education.independent.co.uk

EPSTEIN, D. and JOHNSON, R. (1998) Schooling Sexualities. Buckingham: Open University Press.

EWING, E. (2006) Unreported World, Society Guardian, 16th August. See: www.guardian.co.uk/uk_news/story/0,,1851410,00.html

FBI, FEDERAL BUREAU OF INVESTIGATION (2003) Hate Crime Statistics 2002. Washington DC: US Department of Justice.

FURNISS, C. (2000) Bullying in schools: it’s not a crime – is it? Education and the Law, 12 (1), 9-29.

GADD, D. (2003) Hate and Bias Crime: Criminologically Congruent Law? A review of Barbara Perry’s Hate and Bias Crime: A Reader, The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Criminology, 37(1), 144-154.

GREENE, M.B. (2006) Bullying in Schools: a plea for measure of human rights, Journal of Social Issues, 62(1), 63-79.

HALL, N. (2005) Hate Crime. Cullompton/Devon: Willan Publishing.

HANSARD, UK House of Commons written answers (2005) Anti-Bullying Initiatives. 14th November, Column 927W.

HARI, J. (2006) ‘Gay’ – The Worst Insult in our School Playgrounds, Evening Standard, 18th August, 37.

HAYDEN, C. (2007) Children in Trouble. The role of families, schools and communities. Basingstoke: Palgrave/MacMillan.

HAYDEN, C. (2005) Crime prevention: the role and potential of schools, In WINSTONE, J. and PAKES, F. (Eds.) Community Justice. Cullumpton/Devon: Willan Publishing.

HOME OFFICE (2006a) Crime and Victims – Hate Crime. See: www.homeoffice.gov.uk/crime-victims/reducing-crime/hate-crime/

HOME OFFICE (2006b) Statistics on Race and the Criminal Justice System: A Home Office publication under Section 95 of the Criminal Justice Act 1991. London: Home Office.

JACOBS, J.B. and POTTER, K. (1998) Hate Crimes: Criminal Law and Identity Politics. New York: Oxford University Press.

McDEVITT, J., LEVIN, J. and BENNETT, S. (2002) Hate Crime Offenders: An Expanded Typology. Journal of Social Issues, 58(2), 303-317.

McNEELY, C.A., NONNEMAKER, J.M. and BLUM, R.W. (2002) ‘Promoting School Connectedness: Evidence from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health’, Journal of School Health, 72:4, April, 138-146.

McPHERSON, W. (1999) The Stephen Lawrence Inquiry, Cm 4262. London: The Stationary Office.

MPS, METROPOLITAN POLICE SERVICE (1999) Action Guide To Race/Hate Crime: Consultation Draft. London: Metropolitan Police Service.

MPS (2002) Guide to the Management and Prevention of Critical Incidents. London: MPS.

MORI, MARKET AND OPINION RESEARCH INTERNATIONAL (2004) MORI Youth Survey 2004. London: Youth Justice Board.

NAS/UWT, NATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF SCHOOLMASTERS/UNION OF WOMEN TEACHERS (2003) NASUWT House of Lords victory over violent and disruptive pupils 23rd April.

See: http://www.nasuwt.org.uk/Templates/Internal.asp?NodeID=69320&Arc=0

NYPD, NEW YORK CITY POLICE DEPARTMENT (2002) Hate Crime Task Force 2001 Year End Report. New York: NYPD.

PERRY, B. (2001) In the Name of Hate: Understanding hate crimes. New York: Routledge.

RESNICK, M.D., BEARMAN, P.S. and BLUM, R.W. (1997) ‘Protecting Adolescents from Harm: findings from the National Longitudinal Study on Adolescent Health’, JAMA, 278, 823-832.

SIBBITT, R. (1997) The Perpetrators of Racial Violence and Racial Harassment. Home Office Research Study 176. London: Home Office.

SMITH, P.K. (2000a) School bullying and ways of preventing it, in E. Debarbieux, and C.Blaya (eds) Violence in Schools and Public Policies. Paris: Elsevier, 117-128.

SMITH, P.K. (2002b) (co-ordinator) Bullying. Don’t suffer in silence – an anti-bullying pack for schools. London: DfES.

SMITH, P.K., TALAMELLI, L., COWIE, H., NAYLOR, P. and CHAUHAN, P. (2004) Profiels of non-victims, escaped victims, continuing victims and new victims of school bullying, British Journal of Educational Psychology, 74, 565-581.

SMITH, P.K. and MYRON-WILSON, R. (1998) ‘Parenting and School Bullying’, Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 3:3, 405-417.

SMITH, P.K. and SHARPE, S. (1994) School Bullying: Insights and Perspectives. London: Routledge.

SMITHERS, R. (2005) Teachers' union reveals mounting cost of injury payouts

Guardian Unlimited, 29th March. See : http://education.guardian.co.uk/classroomviolence/story/0,,1447424,00.html

STANKO, E. (2001) Re-conceptualising the Policing of Hatred: Confessions and Worrying Dilemmas of a Consultant. Law and Critique, 12, 3, 309-329.

STEER, A. (2005) (chair) Learning Behaviour. The report of the Practitioners’ Group on School Behaviour and Discipline. London: DfES.

STEIN, N. (2003) Bullying or Sexual Harassment? The missing discourse of rights in an era of zero tolerance, Arizona Law Review, 45, 783-799.

STEWART, W. (2006) Tsar calls for more school discipline, Times Educational Supplement, 29th August.

See: http://www.tes.co.uk/section/story/?_id=2273701&window_type=print

SYKES, G. and MATZA, D. (1957) Techniques of Neutralisation, American Sociological Review, 22, 664–670.

TAYLOR, M. (2006) Twelve years later, a pupil tormented by primary school bullies gets £20,000, The Guardian, 21st February.

See: http://education.guardian.co.uk/pupilbehaviour/story/0,,1714362,00.html

THORPE, L. (2006) Police tackle hate crime in schools, Chard & Illminster News, 13th September.

See: http://www.chardandillminsternews.co.uk/news/cinewschard/display.var.919777.0.pol

VERLINDEN, S., HERSEN, M. and THOMAS, J. (2000) Risk factors in school shootings, Clinical Psychology Review, 20(1), January, 3-56.

VISSER, J. (2006) Keeping violence in perspective, International Journal on Violence and School, 1, May. Online journal: ijvs.org.

Read also

> Fourth world conference : last news !

> Approche comparative franco-canadienne du sport carcéral. Une trêve éducative ? Conditions de pratiques et enjeux autour des utopies "vertueuses" du sport

> Education, violences et conflits en Afrique Subsaharienne. Sources, données d'enquête (Côte d'Ivoire, Burkina Faso) et hypothèses

> Teachers as victims of school violence. The influence of strain and school culture

> Violence in High School. Factors and manifestations from a city in southest Brazil

> Violence in schools: perceptions of secondary teachers and headteachers over time

<< Back