Article

| 5 - Bullying in schools: predictors and profiles. Results of the portugese health behaviour in school-aged children survey by Sónia M. Pedroso Gonçalves, Projecto Aventura Social e Saúde & Centro de Investigação e Intervenção Social, Instituto de Ciências do Trabalho e da Empresa Margarida Gaspar de Matos, FMH, Technical University of Lisbon & CMDT/UNL Theme : International Journal on Violence and School, n°7, December 2008 |

| The purpose of this study was to: analyse predictor variables of bullying behaviours and analyse the association profiles between bullying behaviours, gender and school grade. The database of the Portuguese HBSC study was used comprising a nationally representative sample of 6131 adolescents. The more the students perceive school as being unsafe, more unsatisfied they feel with their lives, more they report to be victims of bullying and more they relate to disturb the colleagues; the same pattern is demonstrated when the students carry weapons, consume tobacco and alcohol. The different types of bullying share the same predictors; however, they have particularities and singularities. The types of bullying behaviour can be grouped in a different ways; and same are typically associated with girls and others with boys, as well as with different school grade. It is expected that the results of this study will raise the awareness to the problem. |

Keywords : Bullying; Bully, Victim, Gender, School grade.

| PDF file here.

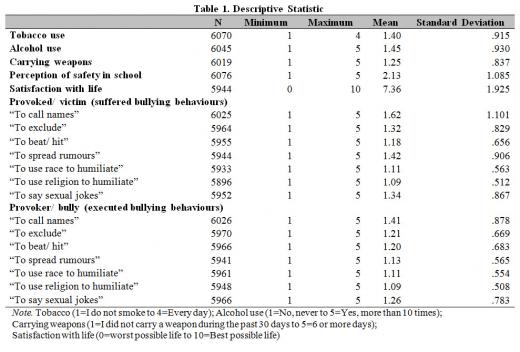

Click on the title to see the text. INTRODUCTION The change that occurs between the childhood and the adolescence is an important stage in life, because it is in this time that occur the formation of self and gender identity. This formation based in part in the relations between the similar, it is when one defines his/ she morality and establish some objectives. The entire environment that surrounds the adolescent determines how he/ she is socialized with his roles and clarifies what is appropriated and what is not. This process influences the adolescent’s actions in stressful situations. For example, the individual’s exposure to the abuse when he was a child or when some family member was abused may be one of the possible factor that conduct to violence. Bullying is one of the most common forms of violence in our society in which one individual dominates and other is perceived as weaker. Men oppress their women, women their children, and the older children oppress the younger. In spite of being considered as violence, bullying has not the necessary attention. For example, most of the groups that work in schools, including teachers, do not face these behaviours as threat or oppression or as violent behaviours. This may be because the society has become more insensitive to the cruelty that is constantly exposed in the information that is everywhere. Therefore, many young people are witnesses of these acts of violence and feelings of inevitability, lack of hope and alienation emerge (Willert & Lenhardt, 2003). Researchers’ attention to bullying is increasing. Bully and victim problems among school children are a matter of considerable concern in many countries. In a study conducted in Australia, about 24% of students are violent to their colleagues, 13% are victims of violence and 22% are simultaneously victim and aggressor (Forero, McLellan, Rissel & Bauman, 1999). Fekkes Pijpers and Verloove-Vanhorick (2005) studying a group of Dutch children, concluded that about 16% of children have been bullied regularly, and about 50% did not tell their teacher what had happened. In the HBSC Portuguese study carried on in 1998 (Matos et al., 2000) and 2002 (Matos et al., 2003, 2004) results suggest that about 1/5 of teenagers had been victims of violence and about 1/5 assume that they had been aggressive. About 1/4 had been simultaneously victims and aggressors, (provocative victims or double status). Those studies indicated that there are some gender differences; hence the percentage of aggressive boys is bigger, compared to the percentage of aggressive girls. DEFINITION OF BULLYING The study of bullying begun with the systematic research of Olweus in the beginning of the 70’s in Norway and Sweden, in which millions of students from the primary, secondary and high school have been inquired. Bullying is considered an intentional behaviour, with the specific goal of doing harm to someone (e.g., DeHaan, 1997; Olweus, 1994). It includes behaviours like calling names, teasing, hitting, kicking, pushing, withdrawing friendship or spreading rumours (Juvonen, Graham & Schuster, 2003); therefore, this damage can be physical, verbal, psychological or sexual (Currie, 2000; Matos et al 2003). This behaviour is always repeated over time (Olweus, 1994) and implies the existence of a certain hierarchy or imbalance of power between victim and aggressor, in which the aggressor sees the victim as someone weaker (Harris & Petrie, 2002; DeHaan, 1997). Most of the time this aggressive behaviour occurs without being provoked (Harris & Petrie, 2002). TYPES OF BULLYING Three types of bullying are considered: the physical or direct, the psychological and the indirect. The physical or direct encloses behaviours such as to hit, to kick, to push, to steal, to threaten, to play in an intimidating way and to use weapons. The psychological one refers to calling names, to tease or to annoy someone, to be sarcastic, insulting or injurious, to make faces and to threaten. At last, the indirect one, less visible, includes to exclude or to reject somebody from a group (Bullock, 2002). PROTOTYPE/ PROFILE OF THE OFFENDER AND THE VICTIM The literature had demonstrated that exist a certain prototype of people who oppress and of the ones that are oppressed. The people who oppress need to have power and to dominate, they like the control that they have on others. They have a positive feeling for violence and little understanding with their victims. Normally they have some popularity and are followed by a small group. Concerning self-esteem there is some controversy. While Olweus (1997) and Rigby and Slee (1995) defend that the individuals in question do not have low auto-esteem, Me (2001, quoted by Isenhagen & Harris, 2004) reported that those with low self-esteem that had been oppressed can later oppress their colleagues. It has been demonstrated that when self-esteem is threatened it increases the violence probability, that is, when an oppressing pupil feels that his/her self-esteem is to be threatened by insults, critiques or injuries his/her reply will be more aggressive than the normal one. The individuals that are included in this group have lack of empathy and abilities to resolve problems (Bullock, 2002). This type of pupils has greater probability to drink alcohol and to smoke cigarettes than their victims, they also suffer from a lesser adjustment in an academic level. Finally, these students are normally higher, stronger, more aggressive, more impulsive and not cooperative (Harris & Petrie, 2002). In turn, people who are oppressed are generally weaker, shyer, more introverted, more cautious, more sensitive, quieter, with lesser self-esteem and have few friends. Me in 2001 (quoted by Chapell et al., 2004) concluded that the students of the secondary with lesser status, ethnic minorities had greater probability to be victims. These individuals also had some probability to smoke cigarettes, to drink alcohol and to have low school performances. When it adult intervention is inexistent, pupils repeatedly tend to be oppressed, run the risk of being rejected, go in depression and have a constant threat to their self-esteem (Bullock, 2002). Thus, two sub-groups exist, while the first one is considered submissive or passive, the second one is considered provocative. The passive victims do not provoke its colleagues, do not like violence, tend to be weaker than other colleagues, react crying or becoming sad (Isenhagen & Harris, 2004). On the other hand, the victims who are provocative are the minority of the victims. Normally they have a deficiency in learning and lack of social abilities that make them become insensitive to other students. These students have trend to be scoffing and to annoy colleagues until somebody be aggressive to them (Harris, Petrie & Willoughby, 2002). PREDICTORS OF BULLYING Having accounted the aspects and the long term effects of bullying, researcher have tried to find the causes and factors of such aggressive behaviours in order to intervene. For example, Finn and Frone (2003) conducted a study in United States of America, in which they studied the relationship between gender and race with aggressive behaviour. These authors had demonstrated that men have greater probability of involving themselves in situations that contemplate aggressive behaviours than women; and, that as much the African-Americans and the Latin-Americans registered more fights in school than the Caucasians. It is important to report that gender differences exist for the aggressive behaviours. The biggest differences occur in the form the aggressive behaviours are executed. While boys use the form of physical aggression over all, girls tend to opt for the psychological forms of aggression or the indirect ones (Young & Sweeting, 2004). The boys are more subdue to violence than girls, however, girls report more often being oppressed victims (Harris & Petrie, 2002). It was also found that boys tend to have more aggressive behaviours than girls (Chapell et al., 2004). Girls can have as many overwhelming behaviours as boys. However, the girls do not want to demonstrate their involvement in these situations, so they use psychological and indirect forms of bullying, this means that it can occur an under-esteem of violent behaviours in this field (Bullock, 2002). Another important factor concerns personality characteristics; when individuals have provoking traces of personality, the probability of involving themselves in physical and verbal aggression increases. People who have low self-control have a bigger tendency to follow the ways of violence; they are considered impulsive and rebellious and had been positively associated with the substance use. It is not confirmed yet that alcohol use causes violent acts; however, there is no doubts that the incidents of aggression and violence are frequently followed by alcohol consumption. Finn and Frone (2003) distinguished between alcohol use during school hours and alcohol consumption out of the school schedule. They concluded that alcohol use during school schedule is related with the interpersonal aggressions and school vandalism. The opposite is not verified, that is, alcohol ingestion out of the context of school is not associated with school aggressions. Students’ academic grade is also an important variable. High-school students enunciated a higher propensity for interpersonal violence, specially when they had a low academic orientation and low grades (Ellickson et al., 1997, cited by Finn & Frone, 2003). CONSEQUENCES OF BULLYING Aggressive relations have consequences for the people who oppress and for the oppressed ones. These effects may be long term (Williams, Chambers, Logan & Robinson, 1996). Oppressors who keep the aggressive behaviour will have difficulty in the future with the development and maintenance of positive relations (Bullock, 2002). Bullies usually have little acceptance from their pairs. They have few friends and they do not feel pleasure about going to school (Due, Holstein & Jorgeensen, 1999; King, Wold, Tudor-Smith & Harel, 1996). Compared to other colleagues, bullies have greater tendency for risk behaviours, such as tobacco abuse (King et al., 1996); alcohol abuse (Due et al, 1999; King et al., 1996) and drugs abuse (DeHaan, 1997). Studies (e.g., Young & Sweeting, 2004) have disclosed that the consequences for the oppressed students are considerable: isolation, physical or psychosomatic symptoms, sadness, anxiety, depression, ideation of suicide and suicide. Other important questions are the fact that the oppressed pupils abandon the school more easily and their performance in school can become lower due to the aggression situation (Isernhagen & Harris, 2004). Like bullies, the victims also have difficulty in finding friends and usually do not feel well at school (DeHaan, 1997; Sudermann et al., 2000). Salmon, James and Smith (1998) defend that the children who suffer the consequences of victimization, present more symptoms of depression and anxiety, compared to other children. In a study that investigated Portuguese teenagers these results are confirmed. The victims present more physical and psychological symptoms, compared with other teenagers (Matos et al, 2004). Rigby (1999) also defends that the victimization can be related to the appearance of physical complaints in adolescents. The most frequent complaints are headaches and abdominal pain (King et al, 1996). Williams, Chambers, Logan and Robinson (1996) found strong association between reported bullying and common health symptoms, such as headaches, tummy ache, feeling sad or very sad, bed wetting, and sleeping difficulties. Bond, Carlin, Thomas, Rubin and Patton (2001) considers that having a past where there are memories of being a victim of bullying can predict the appearance of psychological disturbances, such as anxiety or depression. This study suggests that in a group of adolescents who suffer from depression, about 30% had history of victimization episodes. The negatives consequences of bullying are not limited to the appearance of psychological disturbances in a short-term period. Some authors consider that the effects of victimization can be seen under the form of depression in the adult age (Olweus, 1993). OBJECTIVE OF THE STUDY The objectives of this study are: (1) to analyze the predictor variables of bullying behaviours (while provoked and provoking); and, (2) to analyze the association profiles between these behaviours of bullying, gender and school grade. METHOD PARTICIPANTS AND SAMPLING METHODS Data from the Portuguese second wave of the Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children (HBSC) study, a cross sectional international, WHO collaborative study (e.g., Currie et al., 2004; Matos et al., 2003, 2005), was used for this work. The sample was representative of Portuguese adolescents attending 6th grade, 8th grade, and 10th grade, within the public school system. Private schools were not included. Participants of this study were 6131 students aged 10 to 17 years old (X=14 ± 1.85 years old). From these 6131 students, 51% were girls. Regarding age group, 19% were in the 10-11 years-old group, 34% were in the 12-13 years-old group, 30% were in the 14-15 years-old group and 17% were in the 16 or more years-old group. PROCEDURE This study followed strictly the norms and protocol from the Helsinki Declaration and recommendations from the University board level, and National Commission for Individual Data Protection. Furthermore, all authorizations from the Educational Divisions, schools and parents level were obtained. The questionnaires required 55 minutes to complete and were administered in the classroom by teachers. Students completed the questionnaires on their own. Teachers were given a set of standardized instructions and they did not answer any questions concerning the content of the questionnaire, or looked at pupils’ answers. Pupils’ participation in the survey was voluntary and anonymity was assured. Pupils were asked to put their completed questionnaires in an envelope and the last pupil was requested to seal the envelope. The process of distribution and collection of questionnaires in the entire country was done by mail. The questionnaire consisted of two parts. The main HBSC survey included questions on demographics (age, gender, socio-demographics), school related variables, tobacco and alcohol use, physical activity and leisure, nutrition, safety aspects of psychosocial health, general health symptoms, social relations and social support. A complete picture of previous uses of HBSC items and their psychometric properties can be found in the international study report (Currie et al., 2004). DATA ANALYSIS The analysis of the data was performed with the statistical software SPSS 12. Descriptive statistics, regression analysis for prediction of bullying behaviours, and analysis of HOMALS (Homogeneity Analysis) of the association profiles between bullying behaviours, gender and school degree were performed. RESULTS The results are presented according to the following order: descriptive statistics of the variables, regressions of prediction of bullying behaviours, and finally, analysis of the association profiles between the bullying behaviours, the gender and the scholar year. These behaviours were analyzed in the perspective of the aggressor (provoking) and the attacked one (provoked). Having in account the previous literature revision the following variables were selected (specifically, gender, school grade, tobacco use and alcohol use and carrying weapons, perception of school safety and satisfaction with life), to study their relationships and their predictive power for bullying behaviours. DESCRIPTIVE STATISTICS OF THE BULLYING BEHAVIOURS AND PREDICTORS Seven bullying behaviours had been analyzed: calling names, to exclude, to hit, to spread rumours, to use race or religion to humiliate and to say sexual jokes, in the perspective of who is provoked and of who provokes. Pupils report to be more provoked by the following behaviours of bullying: Calling names, rumours and sexual jokes. The students report that they provoke the colleagues especially calling them names, saying sexual jokes and leaving them out of the activities. Globally, the students of this sample rarely consume tobacco and/or alcohol. They report carrying some kind of weapon during some days of the last month, and tend to consider the school unsafe and are satisfied with life (Table 1).

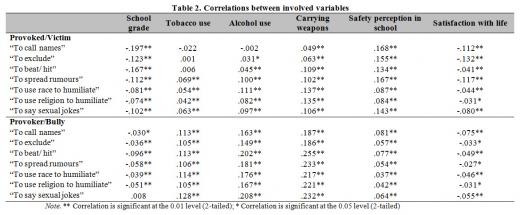

CORRELATIONS BETWEEN THE BULLYING BEHAVIOURS AND PREDICTIVE VARIABLES Table 2 presents the correlations between the types of bullying behaviours studied in the perspective of the provoker and the provoked. The perception of the existing safety in the school and carrying weapons are variables that are positively and significantly associated with all the executed and felt types of bullying; in turn, the satisfaction with life is associated negatively and significantly with all types of bullying. Alcohol use is associated positively and significantly with all the bullying behaviours, except with “calling names” (provoked). Tobacco use is positively and significantly associated with all types of bullying behaviours, except with the behaviours felt by the provoked ones when “calling them names,” “leave them out” and “beat them.” School grade and year is negatively associated with all behaviours, except saying sexual jokes concerning the colleagues.

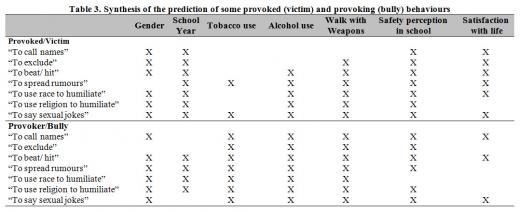

PREDICTION OF BULLYING BEHAVIOURS Regressions had been conducted, in which the dependent variables had been the felt and executed bullying behaviours. The predictive variables had been: the gender, the scholar grade, tobacco and alcohol use and to carry weapons, the perception of school safety and the satisfaction with life. In Table 3 a synthesis of the variables that significantly predict (designated with an x) each type of behaviour can be observed. It is possible to see that the different types of bullying behaviour have different predictors. However, it is important to point out the predictive role of gender, school grade, alcohol use, to carry weapons and the perception of school safety in the different types of bullying behaviours.

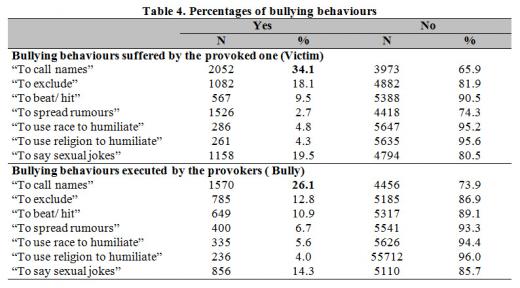

PROFILES OF ASSOCIATION BETWEEN BULLYING BEHAVIOURS AND PREDICTIVE VARIABLES The variables had been recoded so that they could be used in a HOMALS analysis. The purpose of this analysis was to define association profiles between the variables in study (following the previous literature revision it was been selected to study the association with the bullying behaviours, two socio-demographic variables, gender and school grade). Thus, bullying behaviours were categorized in “Yes” (had already suffered or executed the behaviour) and “Not” (had never suffered or executed the behaviour). Table 4 represents the percentage of students that reported to have been bothered or to have bothered by each type of bullying behaviour. Note that the verbal insults are the type of felt and executed bullying in higher percentage.

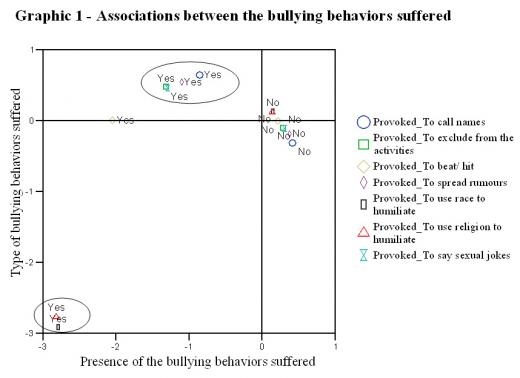

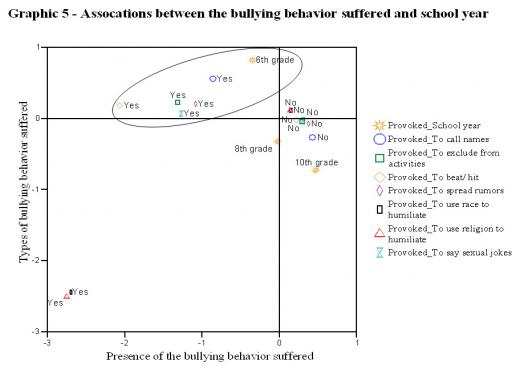

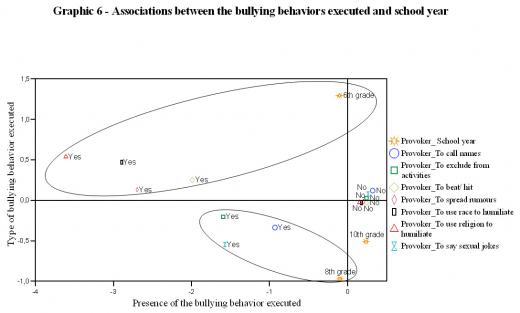

Several HOMALS were performed with the objective to find associations between bullying behaviours, gender and school grade. The two firsts graphics represent the association profiles between the different bullying behaviours suffered (Graphic 1) and executed (Graphic 2). The two second graphics present the associations between the gender and the different bullying behaviours suffered (Graphic 3) and executed (Graphic 4). The two last graphics show the associations between the school grade and the bullying behaviours suffered (Graphic 5) and executed (Graphic 6). Felt and suffered bullying behaviours are grouped in two principals groups, one constituted by the behaviours referring to verbal aggression, and to the exclusion of the activities of the group of colleagues; the other group, is constituted by the aggressions associated to religion and race (Graphic 1).

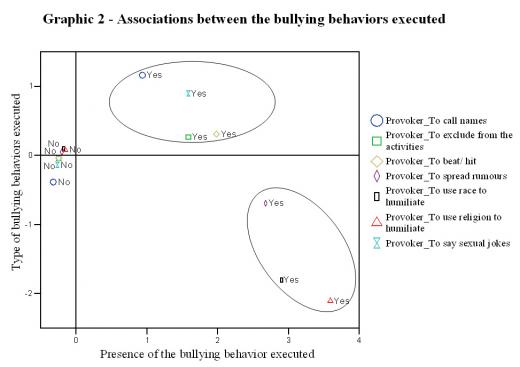

The executed bullying behaviours are also grouped in two groups, the first one is constituted by the physical aggression behaviours, exclusion of the activities, calling names and to say sexual jokes; the second group of behaviours congregates launching rumours about colleagues, using religion and race to offend the colleagues (Graphic 2).

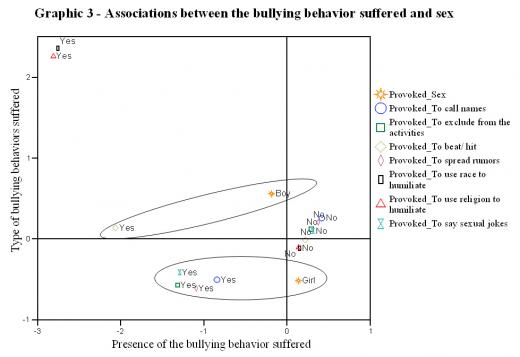

This analysis was repeated, but also including the gender variable to understand if there are types of bullying behaviours more closely associated to the boys than to girls and vice versa. Girls seem to suffer bullying under the form of sexual jokes, rumours, calling names and to be left out of the activities (more psychological and indirect form). The boys in turn suffer a more direct form of bullying, the physical aggression (Graphic 3).

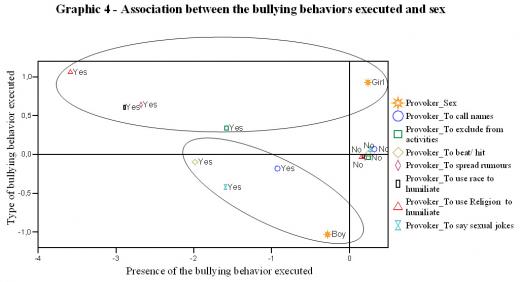

Relatively to the executed bullying behaviours, boys are more likely to hit, call names and say sexual jokes (Graphic 4). The girls seem to be more associated with more psychological bullying (e.g., rumours, to exclude, using race and religion to provoke the colleagues).

Sixth graders reveal to be more associated with suffering the following bullying behaviours: verbal, be called names, to take rumours concerning themselves, saying sexual jokes and to be excluded of the activities (Graphic 5).

Relatively to the executed bullying behaviours on the colleagues, association between the 6th grade and physical aggression and saying rumours about the colleagues and using race and religion against the colleagues can be observed. Tenth graders are mainly associated with verbal behaviours (e.g., call names and say sexual jokes) and an indirect bullying (e.g., exclusion) against the schoolmates (Graphic 6).

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION The purpose of this study was (1) to analyze the predictor variables of bullying behaviours (while provoked and provoking); and, (2) to analyze the association profiles between these behaviours of bullying, gender and age Seven different behaviours of bullying in the perspective of the provoked one and the provoker had been analyzed: calling names, to leave someone out, to hit, rumours, race, religion and sexual jokes. It is important to reinforcing that the pupils feel themselves provoked and say that they provoke others by different forms. The students report to be provoked and to provoke more through verbal insults, rumours, sexual jokes and exclusion (Juvonen, Graham & Schuster, 2003; Bullock, 2002). It seems important to take into account the relationship between the perception of safety in school, the fact of carrying weapons and the satisfaction with life and the bullying behaviours. Thus, the more the students perceive school as being unsafe, the more they report to be victims of bullying and more they relate to disturb the colleagues; the same pattern is verified when the students carry weapons, consume tobacco and alcohol drinks. In turn, the more unsatisfied the pupils are with their lives, the more they felt provoked and the more they provoke. These results can be used in a practical way to fight against the bullying problem. Thus, pupils have to feel themselves safe in the schools, the transport of weapons must be avoided and it is important to contribute for their satisfaction. Considering the results of the regression analysis for prediction of bullying behaviours, it is important to point out that the different types of bullying share the same predictors; however, it has particularities and singularities. This result seems to indicate that the programs of intervention against bullying must take into consideration the type of bullying with which they are acting. The HOMALS analyses show that the types of bullying behaviour group themselves in different forms (e.g., Bullock, 2002), with a more direct dimension (e.g., physical and verbal aggression) and “a more ideological” dimension (e.g., religion and race). This study shows that some types of bullying behaviours are more associated to the boys and others to the girls (e.g., Young & Sweeting, 2004). Thus, girls seem to suffer from bullying under the form of sexual jokes, rumours, calling names and to be left out of the activities. In turn, the boys suffer more from a more direct bullying form, the physical aggression. Relatively to the executed bullying behaviours, boys reveal themselves associated especially with direct bullying (e.g., hitting). In such a way, it seems that boys tend to have more aggressive behaviours than girls (Chapell et al., 2004). The pupils of the 6th grade feel bullying in a more verbal nature, be called names, to be victim of rumours, to say sexual jokes and also the exclusion of activities. Relatively to the executed bullying behaviours on the colleagues, the 6th grade reveals to be associated with direct and psychological bullying behaviour (e.g., hitting and rumours, respectively) and using religion and race against the colleagues; the 10th grade is associated mainly with verbal behaviours against the schoolmates and exclusion. These results denote the importance of starting to act on this problem immediately during earlier school grades. School seems a privileged environment for the implementation of health programs, especially when interventions also emphasized the supporting role of peers and families (Calmeiro & Matos, 2005; Matos, 2005). Frequently, acknowledgement of health-related information or beliefs about lifestyles is, by itself, insufficient to promote change. Educational approaches should focus on developing adolescents’ life skills because often adolescents face tasks that require acquisition of competences, manage emotions, become autonomous, and develop mature relationships and personal integrity (Matos, 2005; Smalley, Wittler, & Oliverson, 2004; Botvin & Griffin, 2004; Danish, Fazio, & Nellen, 2002) in order to cope with daily life and future challenges. Classroom-based training involving instruction, modelling and role-playing can assist students to identify and prepare for roadblocks in the process of resisting social influences and change norms. Emphasis should be placed on perceptions of competence, autonomy and personal efficacy. As several health-damaging behaviours are likely to co-exist, researchers should assess the development, implementation and evaluation of multiple component intervention programs (Calmeiro & Matos, 2005; Matos, 2005; Botvin & Griffin, 2004). The present study has some limitations. First, the variables used in this study were developed post hoc from an existing survey. Second, the findings are based on adolescents’ self-reports, so biases in perception and reporting cannot be ruled out. Notwithstanding these limitations, this study ensured a nationally representative sample. Moreover, to the best of the authors’ knowledge, this study is the first national representative wide in depth investigation about bullying predictors and profiles. In future studies it would be important to complete the quantitative data with the qualitative data; to promote longitudinal studies, which would allow to perceiving the tendencies of the aggressors and the attacked ones, and also the way the victims deal with the bullying situations. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The HBSC study in Portugal in 2001/2004 was funded by FCT/MCT/ 37486/PSI/2001/FEDER, CNIVIHSida, Glaxo and IDT. The authors would like to thank The Portuguese Aventura Social e Saúde team, for their work on data collection and data management. |

Bibliography

BOND, L., CARLIN, J.B., THOMAS, L., RUBIN, K., & PATTON, G., (2001) Does bullying cause emotional problems? A prospective study of young teenagers. BMJ, 323, 480-484.

BOTVIN, G.J., & GRIFFIN, K.W., (2004). Life skills training: Empirical findings and future directions. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 25(2), 221-232.

BULLOCK, J., (2002). Bullying among children. Childhood Education, 78(3), 130-133.

CALMEIRO, L. & MATOS, M., (2005). Psicologia do Exercício e da Saúde [Psychology of exercise and health]. Lisboa: Visão & Contextos.

CHAPELL, M. et al., (2004). Bullying in college by students and teachers. Adolescence, 39(153), 53-65.

CURRIE, C., HURRELMANN, K., SETTERTOBULTE, W., SMITH, R., & TODD, J., (2000). Health and health behaviour among young people. HEPCA series: World Health Organization.

CURRIE, C., SAMDAL, O., BOYCE, W., & SMITH, R., (2001). HBSC, a WHO cross national study: Research protocol for the 2001/2002 survey. Copenhagen: WHO.

CURRIE, C., ROBERTS, C., MORGAN, A. et al., (2004). Young people health in context. Copenhagen: WHO.

DANISH, S., FAZIO, R., NELLEN, V. et al., (2002). Teaching Life skills through sport: Community-based programs to enhance adolescent development (pp.269-288). In VAN RAALT & BREWER (Eds.). Exploring Sport and Exercise Psychology. Second Edition. Washington, DC: APA.

DEHAAN, L., (1997). Bullies. Retrieved May 24, 2000 from World Wide Web: ndsuext.nodak.edu

DUE, E., HOLSTEIN, B., & JORGENSEN, P., (1999). Bullying as health hazard among school children. Retrieved February 14, 2000 from World Wide Web: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov:80

FEKKES, M., PIJPERS, F. & VERLOOVE-VANHORICK, (2005).Bullying: who does what, when and where? Involvement of children, teachers and parents in bullying behaviour. Health Education Research, 20(1), 81-91.

FINN, K., & FRONE, M., (2003). Predictors of aggression at school: The effect of school-related alcohol use. National Association of Secondary School Principals. NASSP Bulletin.

FORERO, R., MCLELLAN, L., RISSEL, C., & BAUMAN, A., (1999). Bullying behaviour and psychosocial health among school students in New South Wales, Australia: Cross sectional survey. BMJ, 319, 344 –348.

HARRIS, S., & PETRIE, G. (2002). A study of bullying in the middle school. National Association of Secondary School Principals. NASSP Bulletin, 86, 42-53.

HARRIS, S., PETRIE, G., & WILLOUGHBY, W., (2002). Bullying among 9th graders: An exploratory study. National Association of Secondary School Principals. NASSP Bulletin, 86, 3-14.

ISERNHAGEN, J. & HARRIS, S., (2004). A comparison of bullying in four rural middle and high schools. The Rural Educator, 25 (3), 5-13.

JUVONEN, J., GrAHAM, S. & ScHUSTER, M., (2003). Bullying Among Young Adolescents: The Strong, the Weak, and the Troubled. Pediatrics, 112, (6) 1231-1237.

KING, A., WOLD, B., TUDOR-SMITH, C., & HAREL, Y., (1996). The health of youth: A cross-national survey. Canada: World Health Organization.

MATOS M.G., Equipa do Projecto Aventura Social e Saúde, (2003). A saúde dos adolescentes portugueses - Quatro anos depois [Portuguese adolescents health - four years later]. Lisboa: Edições Faculdade de Motricidade Humana.

Matos M.G., Simões C, BRANCO J. et al., (2004). Risco e protecção: O adolescente, os amigos, a família e a escola [Risk and protection: Adolescent, peers, family and school]. Available at: www.fmh.utl.pt/aventurasocial. Accessed May 18, 2005.

MATOS, M.G. & Team of the Aventura Social Project, (2004). Risco e Protecção [Risk and Protection]. Available in www.fmh.utl.pt/aventurasocial. Accessed June 18, 2005.

MATOS, MG (Eds)., (2005). Comunicação, gestão de conflitos e saúde na escola [Communication, conflict management and health in schools]. Lisboa: CDI, FMH.

OLWEUS, D., (1993). Bullying at school. Oxford e Cambridge: Blackwell.

OLWEUS, D., (1994). Annotation: bullying at school: basic facts and effects of a school based intervention program. Journal of Psychology and Psychiatry, 43 (7), 1171-1190.

RIGBY K., (1999). Peer victimisation at school and the health of secondary school students. Br J Educ Psychol., 69, 95-104.

SALMON, G., JAMES, A. & SMITH, D.M., (1998). Bullying in schools: Self reported anxiety, depression, and self esteem in secondary school children. BMJ, 317, 924-925.

SMALLEY, S.E., WITTLER, R.R, & OLIVERSON, R., (2004). Adolescent Assessment of Cardiovascular Heart Disease Risk Factor Attitudes and Habits. Journal of Adolescent Health, 35, 374-379.

WARREN, K., SCHOPPELREY, S., MOBERG, P., & MCDONALD, M., (2005). A model of contagion through competition in the aggressive behaviors of elementary school students. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 33 (3), 283-292.

WEINHOLD, B., (2000). Uncovering the hidden causes of bullying and school violence. Counseling and Human Development, 32 (6), 1-18.

WILLERT, H.J. and LENHARDT, A.M.C., (2003). Tackling School Violence Does Take the Whole Village. The Educational Forum, 67, 110-118.

WILLIAMS, K., CHAMBERS, M., LOGAN, S., ROBINSON, D., (1996). Association of common health symptoms with bullying in primary school children. BMJ, 313, 17-19.

YANOWITZ, K., & WEATHERS, K., (2004). Do boys and girls act differently in the classroom? A content analysis of student characters in educational psychology textbooks. Sex Roles: A Journal of Research, 51 (1-2), 101-107.

YOUNG, R., & SWEETING, H., (2004). Adolescent bullying, relationships, psychological well-being, and gender-atypical behaviour: A gender diagnosticity approach. Sex Roles: A Journal of Research, 50 (7-8), 525-537.

BOTVIN, G.J., & GRIFFIN, K.W., (2004). Life skills training: Empirical findings and future directions. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 25(2), 221-232.

BULLOCK, J., (2002). Bullying among children. Childhood Education, 78(3), 130-133.

CALMEIRO, L. & MATOS, M., (2005). Psicologia do Exercício e da Saúde [Psychology of exercise and health]. Lisboa: Visão & Contextos.

CHAPELL, M. et al., (2004). Bullying in college by students and teachers. Adolescence, 39(153), 53-65.

CURRIE, C., HURRELMANN, K., SETTERTOBULTE, W., SMITH, R., & TODD, J., (2000). Health and health behaviour among young people. HEPCA series: World Health Organization.

CURRIE, C., SAMDAL, O., BOYCE, W., & SMITH, R., (2001). HBSC, a WHO cross national study: Research protocol for the 2001/2002 survey. Copenhagen: WHO.

CURRIE, C., ROBERTS, C., MORGAN, A. et al., (2004). Young people health in context. Copenhagen: WHO.

DANISH, S., FAZIO, R., NELLEN, V. et al., (2002). Teaching Life skills through sport: Community-based programs to enhance adolescent development (pp.269-288). In VAN RAALT & BREWER (Eds.). Exploring Sport and Exercise Psychology. Second Edition. Washington, DC: APA.

DEHAAN, L., (1997). Bullies. Retrieved May 24, 2000 from World Wide Web: ndsuext.nodak.edu

DUE, E., HOLSTEIN, B., & JORGENSEN, P., (1999). Bullying as health hazard among school children. Retrieved February 14, 2000 from World Wide Web: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov:80

FEKKES, M., PIJPERS, F. & VERLOOVE-VANHORICK, (2005).Bullying: who does what, when and where? Involvement of children, teachers and parents in bullying behaviour. Health Education Research, 20(1), 81-91.

FINN, K., & FRONE, M., (2003). Predictors of aggression at school: The effect of school-related alcohol use. National Association of Secondary School Principals. NASSP Bulletin.

FORERO, R., MCLELLAN, L., RISSEL, C., & BAUMAN, A., (1999). Bullying behaviour and psychosocial health among school students in New South Wales, Australia: Cross sectional survey. BMJ, 319, 344 –348.

HARRIS, S., & PETRIE, G. (2002). A study of bullying in the middle school. National Association of Secondary School Principals. NASSP Bulletin, 86, 42-53.

HARRIS, S., PETRIE, G., & WILLOUGHBY, W., (2002). Bullying among 9th graders: An exploratory study. National Association of Secondary School Principals. NASSP Bulletin, 86, 3-14.

ISERNHAGEN, J. & HARRIS, S., (2004). A comparison of bullying in four rural middle and high schools. The Rural Educator, 25 (3), 5-13.

JUVONEN, J., GrAHAM, S. & ScHUSTER, M., (2003). Bullying Among Young Adolescents: The Strong, the Weak, and the Troubled. Pediatrics, 112, (6) 1231-1237.

KING, A., WOLD, B., TUDOR-SMITH, C., & HAREL, Y., (1996). The health of youth: A cross-national survey. Canada: World Health Organization.

MATOS M.G., Equipa do Projecto Aventura Social e Saúde, (2003). A saúde dos adolescentes portugueses - Quatro anos depois [Portuguese adolescents health - four years later]. Lisboa: Edições Faculdade de Motricidade Humana.

Matos M.G., Simões C, BRANCO J. et al., (2004). Risco e protecção: O adolescente, os amigos, a família e a escola [Risk and protection: Adolescent, peers, family and school]. Available at: www.fmh.utl.pt/aventurasocial. Accessed May 18, 2005.

MATOS, M.G. & Team of the Aventura Social Project, (2004). Risco e Protecção [Risk and Protection]. Available in www.fmh.utl.pt/aventurasocial. Accessed June 18, 2005.

MATOS, MG (Eds)., (2005). Comunicação, gestão de conflitos e saúde na escola [Communication, conflict management and health in schools]. Lisboa: CDI, FMH.

OLWEUS, D., (1993). Bullying at school. Oxford e Cambridge: Blackwell.

OLWEUS, D., (1994). Annotation: bullying at school: basic facts and effects of a school based intervention program. Journal of Psychology and Psychiatry, 43 (7), 1171-1190.

RIGBY K., (1999). Peer victimisation at school and the health of secondary school students. Br J Educ Psychol., 69, 95-104.

SALMON, G., JAMES, A. & SMITH, D.M., (1998). Bullying in schools: Self reported anxiety, depression, and self esteem in secondary school children. BMJ, 317, 924-925.

SMALLEY, S.E., WITTLER, R.R, & OLIVERSON, R., (2004). Adolescent Assessment of Cardiovascular Heart Disease Risk Factor Attitudes and Habits. Journal of Adolescent Health, 35, 374-379.

WARREN, K., SCHOPPELREY, S., MOBERG, P., & MCDONALD, M., (2005). A model of contagion through competition in the aggressive behaviors of elementary school students. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 33 (3), 283-292.

WEINHOLD, B., (2000). Uncovering the hidden causes of bullying and school violence. Counseling and Human Development, 32 (6), 1-18.

WILLERT, H.J. and LENHARDT, A.M.C., (2003). Tackling School Violence Does Take the Whole Village. The Educational Forum, 67, 110-118.

WILLIAMS, K., CHAMBERS, M., LOGAN, S., ROBINSON, D., (1996). Association of common health symptoms with bullying in primary school children. BMJ, 313, 17-19.

YANOWITZ, K., & WEATHERS, K., (2004). Do boys and girls act differently in the classroom? A content analysis of student characters in educational psychology textbooks. Sex Roles: A Journal of Research, 51 (1-2), 101-107.

YOUNG, R., & SWEETING, H., (2004). Adolescent bullying, relationships, psychological well-being, and gender-atypical behaviour: A gender diagnosticity approach. Sex Roles: A Journal of Research, 50 (7-8), 525-537.

Read also

> Summary

> 1 - A new definition and scales for indirect aggression in schools

> 2 - Impact of school context on violence at schools

> 3 - La violence à l'école : ça vaut le coup d'agir ensemble !

> 4 - School violence in an international context : a call for global collaboration in research and prevention

<< Back