Article

| 1 - A new definition and scales for indirect aggression in schools by Mitsuru Taki, National Institute for Educational Policy Research, Japan Phillip Slee, Flinders University, Australia Shelley Hymel, British Columbia University, Canada Debra Pepler, North York University, Canada Hee-og Sim, Kunsan University, Korea Susan Swearer, University of Nebraska, USA Theme : International Journal on Violence and School, n°7, December 2008 |

| In this article, utilizing the concept of "Indirect aggression", the authors give the new perspective to the bullying issues and show the results from the longitudinal comparative survey based on the new perspective. In first section, overviewing the confusion and conflicts in bullying research, the new perspective to the bullying concept are shown. The key concept is "Indirect aggression". In second section, the new definition and scales for the bullying of "Indirect aggression" are explained. The necessity of longitudinal survey is also discussed. In third section, the results from the longitudinal survey are shown. The stability of victims and assailants are testified and six types of bullying are compared among five countries. The main findings are as follows. (1) There is no stability of victims and assailants in the bullying of "Indirect aggression". It means that the intervention should be developed against whole children but not only the high-risk children. (2) The typical type of the bullying of "Indirect aggression" is different among countries. It depends on the culture as like the tolerance of physical violence. |

Keywords : Bullying, Indirect aggression, Longitudinal survey, Comparative survey.

| PDF file here.

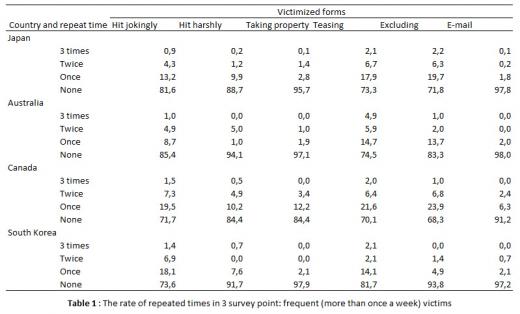

Click on the title to see the text WHY WE NEED THE NEW DEFINITION AND SCALES FOR "INDIRECT AGGRESSION"? THE CONFUSION AND CONFLICTS FROM DIVERSE BULLYING IMAGES Recently bullying becomes a common word all over the world. Many people notice that bullying issues are so serious in school. However, the concept of bullying has wide range of images among people. The discussions based on different images cause unnecessary confusion and conflict. Two typical conflicts are as follows. On the evaluation of Olweus program against bullying Olweus (1993) affirms that it is effective in Norway. Smith (1999) refers that it is effective more to boys than girls in UK. Taki (2000) criticizes that it is useless in Japan. On the cause of bullying Olweus (1993) affirms that the roles of victims and bullies are stable for a long time and rearing condition is a main cause of bullying. Taki (1992, 2001) concludes from his data that most of children become bullies and victims and their roles are not stable, so the personal factors such as rearing condition are not main cause of bullying. Though substantial contraries seem to be among those conflicting opinions, there might be only discrepancies of bullying images. To dissolve the confusion and conflict from diverse images, many researchers use the sub-category of bullying as like physical, verbal, psychological, relational and so on. Furthermore, Olweus (1993) re-categorizes them to direct bullying and indirect bullying. However, listing several sub-categories of bullying form often make the essence of bullying indefinite. WHAT SHOULD BE DISCUSSED AS BULLYING? To make the discussion fruitful, we need to clear what kinds of behaviours should be discussed as bullying. The comparison of the bullying researches between Japan and Europe will be helpful in considering the issues. Japan Japanese research on bullying started in 1980s. A new kind of violence in school attracted people's attention after the school violence in 1970s had been extinguished. Japanese researchers named it "Ijime" and differentiated it from precedent violence. The typical image of precedent violence is the act to damage someone or his/her property physically as like hitting, kicking, robbing, breaking and so on. If someone carries out it in public, he/she is easily punished by usual criminal law. On the contrary, the typical image of "Ijime" is the act to damage someone mentally as like ignoring, excluding, threatening, sending bad mouth by e-mail and so on. Even if someone carries out it in public, he/she is not always punished by usual criminal law. The form and the damage of bullying are invisible. Furthermore, the victims tend to hide their disgrace by some reasons. Therefore, "Ijime" is hard to be noticed by the third person. However, the mental suffering by “Ijime” is as serious as physical suffering. To focus on this new kind of dangerous violence in school, Japanese researcher used the different term "Ijime" from violence. Especially in academic research, there was a clear line between "Ijime" and precedent violence. Europe European academic research with the word bullying started in 1980s. However, they took over old aggression researches called "Mobbning" in 1970s. The old findings showed that the assailants of "Mobbning" were the high-risk boys with personal and/or family trouble. Of course, bullying is not the same as "Mobbning". It includes not only the infliction by a group but also by a single individual. It includes not only the infliction by extraordinary boys but also by ordinary boys and girls. As a result, it includes various behaviours from hitting to ignoring. Nevertheless, the old findings based on the extraordinary boys' "Mobbning" in 1970s were quoted to explain the whole bullying behaviours by boys and girls in 1980s and later. There was neither enough intention to distinguish bullying from "Mobbning" nor from usual violence. Sometimes, 'Repeat' and 'Imbalance in strength' are mentioned as the different characteristics of bullying from violence. However, they cannot distinguish bullying from violence, for some violence is done repeatedly and any violence might be done at some advantages. INTRODUCING THE CONCEPT OF "INDIRECT AGGRESSION" To explain the difference of bullying research between Japan and Europe, the concept of "Indirect aggression" is useful. The concept defined as 'the infliction of psychological damage' comes from Lagerspets, K. M. J., Björkqvist, K. and Peltonen, T. (1988). The distinction between direct aggression and indirect aggression is not same as the distinction between direct bullying and indirect bullying by Olweus (1993). The latter emphasizes the different forms of bullying but the former does the different aims or damage of aggression. So, the authors redefine "Indirect aggression" as 'the infliction of psychological damage regardless of the usage of physical power, psychological power or the others'. Because most of assailants of "Indirect aggression" choose the easiest way to attain the aim i.e. "Low risk and high return". The chosen form is often affected by the accessibility in their cultural context and is not meaningful itself. "Ijime" in Japan is a typical "Indirect aggression". On the contrary, bullying in Europe consists of "Indirect aggression" and direct aggression. This is the reason why, in Europe, there was no clear line between bullying and precedent violence THE TROUBLES OF NO CLEAR DISTINCTION BETWEEN "INDIRECT AGGRESSION" AND DIRECT AGGRESSION No distinction between "Indirect aggression" and direct aggression on bullying results in some troubles. Two examples are shown below. Overleaping the bullying of "Indirect aggression" Most of people tend to judge direct aggression is more serious than "Indirect aggression". "Indirect aggression" is easily overleaped when direct aggression and "Indirect aggression" happen at the same time. For example, 'neglect' in domestic violence is as serious as 'physical punishment', but it is hard for many people to understand that. Visible attack and the physical scars seem serious, but invisible attack and the mental scars do not so much. If hard violence, especially with a kind of weapon, happens daily, people's attentions are easily arrested to hard violence but not bullying. In the same way, if physical bullying happens daily, people's attention are easily arrested to physical bullying but not social bullying. It means that the bullying of "Indirect aggression" is easily overleaped. Wrong intervention against the bullying of "Indirect aggression" The assailant of "Indirect aggression" is not similar to the one of direct aggression. Direct aggression usually needs physical power and/or a kind of weapon. It means that not everybody can join to bullying like direct aggression. On the contrary, "Indirect aggression" does not need any physical power and/or any kind of weapon. It means that anybody can easily join to the bullying of "Indirect aggression". Especially, it is quite easy for children to join calling names by anonymous e-mail. Therefore, the target of intervention against the bullying of "Indirect aggression" should be different from direct aggression. The intervention against the bullying of direct aggression usually targets the extraordinary high-risk children. On the contrary, the intervention against the bullying of "Indirect aggression" should target whole children. If people only target the extraordinary children to reduce the bullying of "Indirect aggression", the intervention might result in failure. The different evaluations on the Olweus program mentioned above are a good example for the mismatched intervention against the bullying of "Indirect aggression". The program works against boys' bullying i.e. direct aggression but not girls' bullying or "Ijime" i.e. "Indirect aggression". To avoid the troubles like above, developing the new definition of bullying focusing on the side of "Indirect aggression" should be required. A LONGITUDINAL SURVEY WITH NEW DEFINITION AND SCALES NEW DEFINITION AND SCALES FOCUSING ON "INDIRECT AGGRESSION" The International Bullying Survey Project (NIER project) developed the new definition and scales focusing on the bullying of "Indirect aggression" with the collaboration of other international researchers. The characteristics of the definition and scales are no usage of direct words, such as bullying in English, "Ijime" in Japanese and "Wang-ta" in Korean, to avoid their old confused images. The new definition was based on the definition of Taki (2003) as below. ' Ijime bullying' is mean behaviour or a negative attitude that has clear intention to embarrass or humiliate others who occupy weaker positions in a same group. It is assumed to be a dynamic used to keep or recover one's dignity by aggrieving others. Consequently, its main purpose is to inflict mental suffering on others, regardless of the form such as physical, verbal, psychological and social.' The three conditions for serious 'Ijime bullying' are: (1) membership, (2) the power of exchangeable status, and (3) frequency of victimization. The word 'Ijime-bullying' in the definition above is used for emphasizing that it is considered almost similar to bullying, but typically refers to "Indirect aggression". Therefore, students were provided with the following explanation before completing the questionnaire. Students can be very mean to one another at school. Mean and negative behaviour can be especially upsetting and embarrassing when it happens over and over again, either by one person or by many different people in the group. We want to know about times when students use mean behaviour and take advantage of other students who cannot defend themselves easily. Following the explanation, students answered questions about experiences with victimizing others and victimization from others. Examples of types of victimization were provided for the students so the extent of their victimization experience could be assessed through rating from 'never' to 'several a week' in 5 points the following; ● physically ( for example, hitting, kicking, spitting, slapping, pushing you[them] or doing other physical harm, on purpose, jokingly); ● physically ( for example, hitting, kicking, spitting, slapping, pushing you[them] or doing other physical harm, on purpose, harshly); ● by taking things from you[them] or damaging your[their] property; ● verbally ( for example, teasing, calling you[them] names, threatening, or saying mean things to you[them]); ● socially ( for example, excluding or ignoring you[them], spreading rumours or saying mean things about you[them] to others or getting others not to like you[them]); ● by using computer, email or phone text messages to threaten you[them] or make you[them] look bad. Those expressions are for victimization and the word in [ ] are used for victimizing. The six types are set to be comparable with the type of precedent bullying research. However, the type "physically" is divided to "jokingly" and "harshly". They are used to capture the subtle difference between bullying that is masked by ambiguous action (e.g. bumping into someone) and bullying that is intentionally hurtful (e.g. a direct push). WHY LONGITUDINAL SURVEY? The NIER project conducted a longitudinal survey involving three waves of data collection. In Japan, some researches based on a longitudinal survey shows that "Ijime" happen among most of children. Taki (1992) pointed out it by three waves longitudinal data from 1985 to 1987 and Taki (2001) did it from by six waves data 1998 to 2000. NIER and MEXT (2005) also show the evidence by twelve waves data from 1998 to 2003. However, there are few longitudinal surveys conducted in other countries and no evidence like Japan. The discussions on direct aggression assume implicitly that the assailants are the high-risk children with family and/or personal troubles. People tend to apply such implicit assumption to the discussion of "Indirect aggression", too. To show whether such implicit assumption to "Indirect aggression" is wrong or not, longitudinal survey is easy and essential. If there are many extraordinary assailants in "Indirect aggression", they might appear repeatedly among waves of the longitudinal survey. On the contrary, if assailants change at each wave of the longitudinal survey, it means that there are no extraordinary assailants in "Indirect aggression". Therefore, the three waves of data collection spanning 18 months was the minimum condition for the project. PARTICIPANTS The participants for the current study were fifth grade students from four countries, including Japan, Australia, Canada, and South Korea. 823 children in Japan, 103 in Australia and 146 in South Korea were collected from Spring in 2004 to Spring in 2005, 205 in Canada from Fall in 2005 to Fall in 2006. 119 in USA Fall in 2005 are also used later. DISCUSSION The stability of victims and assailants among three waves As mentioned above, old bullying research, e.g. Olweus (1993) described the stability of bullies and victims, and concluded rearing condition as the main cause of bullying. His recognition was based on the findings from old "Mobbning" research i.e. direct aggression. The authors show below how different the bullying of "Indirect aggression" is. Table 1 through 4 indicate the frequency in which children were involved in bullying for each survey time point in three waves of longitudinal survey. Of course, they were asked their experience of the bullying of "Indirect aggression" by the questionnaire without the direct words like bullying or "Ijime". If the extraordinary children who have family and/or personal innate problems become assailants and/or victims, their status should be stable. In other words, the same children should appear repeatedly as assailant and/or victim at every survey point. First, in Table 1 and 2, only the frequencies of children who answer their experiences are 'more than once a week' are shown. They are named as the "frequent victims" and the "frequent assailants". If the existence of extraordinary children is the main cause of bullying, such children may answer that their experience are more frequent i.e. at least 'more than once a week'. Second, in Table 3 and 4, the whole children who answer any extent of experiences are shown to make sure of the evidence. Table 1 for "frequent victims" indicates that only a few (2 to 5%) children who are victimized 'more than once a week' at every survey point are in the form of 'teasing' in any countries but few children (less than 2%) are in other forms in any countries with the exception of 'excluding' form in Japan. In short, most of the "frequent victims" only indicated a single experience through the three survey points. It is hard to premise the existence of stable victims from these results. Even if a few children with three times experiences are treated as extraordinary ones, they cannot explain whole bullying incidents because they are only small part of the whole frequent victims in three waves.

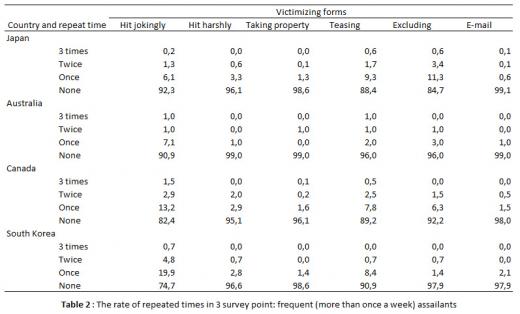

Table 2 for "frequent assailants" indicates that few (less than 2%) children who victimize others at any survey points are in any forms in any countries. In short, most of the frequent assailants have only single experience in three survey points. It is therefore equally difficult to premise the existence of stable assailants, as it was for stable victims.

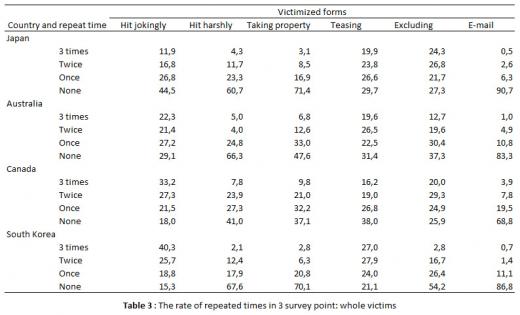

Table 3 shows whole children who answered victimization at any extent (i.e. 'more than once in this term' rather than 'more than once a week'). The results show that many (more than 20%) children victimized at any survey points are in some forms in any countries. For instance, in Japan, 20 to 25% of children were victimized repeatedly by 'teasing' and 'excluding'. However, in such forms of bullying, as if stable victims exist, many other children (totally more than 70%) have been victimized at least once within one and a half year. Although many repeated victims can be found in the form of 'hit jokingly' and 'teasing' in Australia, in the form of 'hit jokingly' and 'excluding' in Canada and in the form of 'hit jokingly' and 'teasing' in South Korea, more other children (totally more than 70%) also have been victimized at least once within one and a half year. Even if the children who experienced bullying at all three periods are treated as extraordinary ones, they can explain only a part of the whole bullying incidents.

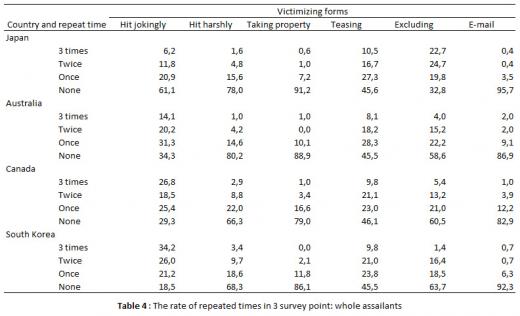

Table 4 shows that whole children who answered victimizing others at any frequency levels. The results show similar tendencies to that of victims. Although many repeated assailants can be found in the form of 'excluding' in Japan and in the form of 'hit jokingly' in the other countries, more other children (totally more than 70%) also have victimized others at least once within one and a half year.

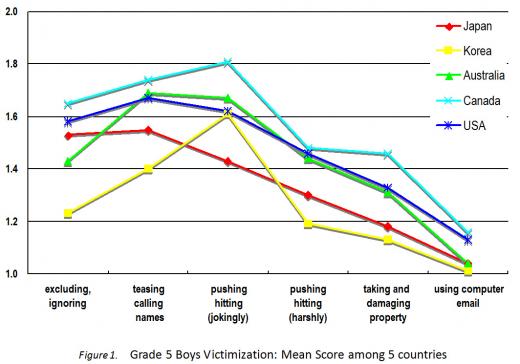

These results are similar to Taki (1992, 2001) and NIER and MEXT (2005). We should not apply the findings from the research of direct aggression to the explanation of "Indirect aggression" without new tests. On the bullying of "Indirect aggression", we should construct the new causality with the premise that most of assailants and victims are ordinary children and their statuses are not always stable. In short, we need to restart the discussion on the bullying of "Indirect aggression". The bullying of direct aggression might be understood in the context of the precedent violence. However, the new causality model and the intervention for the bullying of "Indirect aggression" should be developed. THE COMPARISON OF MEAN SCORE BY TYPE AMONG FIVE COUNTRIES A previous international comparative survey with the questionnaire based on the Olweus was conducted among Japan, England, the Netherlands, and Norway in 1990s (Morita, 2001). The equivalent translated questionnaires were utilized among countries. It means that the word “Ijime” was used in Japan and the word bullying in England. However, Kanetsuna and Smith (2002) pointed out that Japanese children generally have an image of less physical behaviour from the word "Ijime", whereas English children often have a more direct and physical image from the word 'bullying'. Even if Europe and Japan use the same questionnaire, it is possible that Japanese children imagine the bullying of "Indirect aggression" by the translated questionnaire but European imagine mainly the bullying of direct aggression. If such mismatch happened, the difference among countries might come from the bias of images but not the real incident. The questionnaire of NIER project does not contain any direct words as like bullying or "Ijime". Utilizing the questionnaire, we can compare correctly the bullying of "Indirect aggression" among countries. Figure 1 through 4 show the mean scores of each types among countries. The answer of the experience of victimization and victimizing is scored as below; 'more than a week'=3, 'none'=1 and the others 'sometimes'=2. Figure 1 shows the results of victimization in boys. Canada and USA show the similar patterns. The types 'teasing and calling names' and 'pushing and hitting (jokingly)' are highest and 'excluding and ignoring' follows at the almost same level. The types 'pushing and hitting (harshly)' and 'taking and damaging property' are the second group and 'using computer and e-mail' is the least. Australia shows almost the same pattern as Canada and USA, but 'excluding and ignoring' is the second group. Japan has also the similar pattern but physical or criminal type, i.e. 'pushing and hitting (jokingly)’, 'pushing and hitting (harshly)' and 'taking and damaging property', are low. Only Korea has a different pattern. The scores are respectively lower than other countries but 'pushing and hitting (jokingly)' is as high as other countries.

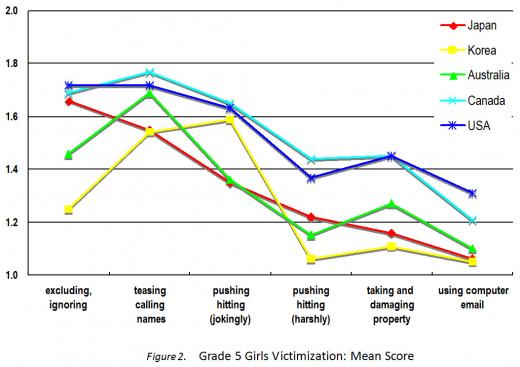

Figure 2 shows the results of victimization in girls. Canada and USA also show the similar patterns but a little different from the boys. The types 'excluding and ignoring' and 'teasing and calling names' are highest and 'pushing and hitting (jokingly)' follows at the almost same level. The types 'pushing and hitting (harshly)' and 'taking and damaging property' are the second group and 'using computer and e-mail' is the least. Girls look less physical a little than boys. Australia shows almost the same pattern as Canada and USA, but 'excluding and ignoring' is the second group like the boys and 'pushing and hitting (jokingly)' is also second group. Japan has also the similar pattern but 'excluding and ignoring' is the highest and 'teasing and calling names' follows. Physical or criminal type, i.e. 'pushing and hitting (jokingly)', 'pushing and hitting (harshly)' and 'taking and damaging property', are as low as the boys are. Only Korea has a different pattern. The scores are respectively lower than other countries, but 'pushing and hitting (jokingly)' is as high as other countries. Furthermore, the type 'teasing and calling names' is higher than the boys are.

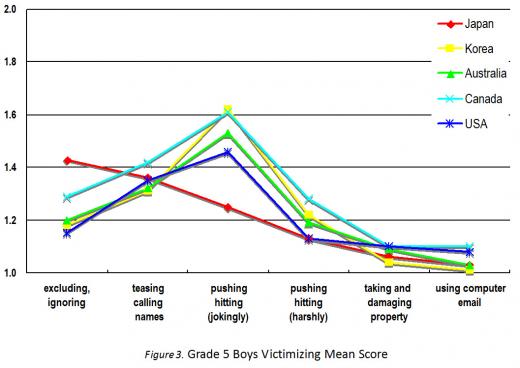

Those results suggest the cultural difference among countries. The tolerance of the employing of physical violence might affect the choice of the way. The results of victimizing support this hypothesis strong. Figure 3 shows the results of victimizing in boys. Australia, Canada, Korea and USA show the similar patterns. The type 'pushing and hitting (jokingly)' is the highest and 'teasing and calling names' follows. The types 'excluding and ignoring' and 'teasing and hitting (harshly)' are the second group. The types 'taking and damaging property' and 'using computer and e-mail' are the least. Korea shows the highest 'pushing and hitting (jokingly)' among five countries. Japan shows the highest 'excluding and ignoring' and 'teasing and calling names' are the same level as the other countries. The Japanese pattern is as same as the victimization and physical or criminal type, i.e. 'pushing and hitting (jokingly)', 'pushing and hitting (harshly)' and 'taking and damaging property', are low.

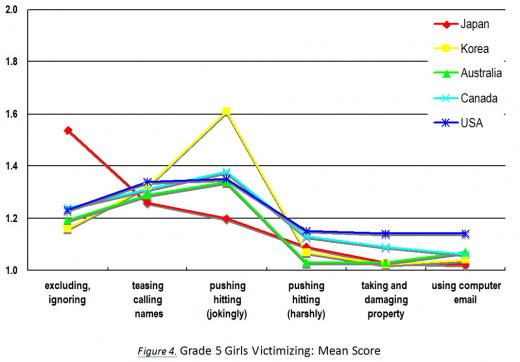

Figure 4 shows the results of victimizing in girls. Australia, Canada and USA show the similar patterns. The types 'teasing and calling names' and 'pushing and hitting (jokingly)' are highest and 'excluding and ignoring' follows at almost the same level. The types 'pushing and hitting (harshly)' and 'taking and damaging property' and 'using computer and e-mail' are the second group. Australia shows less criminality than Canada and USA in the second group types, i.e. 'pushing and hitting (harshly)' and 'taking and damaging property'. Korea is almost the same as the three countries, but shows the highest 'pushing and hitting (jokingly)' among five countries. Japan shows the highest 'excluding and ignoring' and 'teasing and calling names' at the same level as the other countries. The Japanese pattern is as same as the victimization and physical or criminal type, i.e. 'pushing and hitting (jokingly)', 'pushing and hitting (harshly)' and 'taking and damaging property' are low.

The authors mentioned above that most of assailants of "Indirect aggression" choose the easiest way to attain the aim i.e. "Low risk and high return" and the chosen form are often affected by the accessibility in their cultural context. The results above support the opinion. It means that cyber bullying will grow up soon and another new way of bullying of ‘Indirect aggression’ will appear in future. CONCLUSION The authors discussed that the diverse bullying images caused the confusion and conflicts in bullying research and suggested that the key concept to dissolve the confusion and conflicts was "Indirect aggression". The new definition and scales that focus on the side of "Indirect aggression" and avoid the bias of translation are explained and the necessity of the longitudinal survey was discussed. The results from the longitudinal survey with the questionnaire based on the new definition and scales were good for comparison among countries and suggestive to understand the essence of bullying and the affection by culture. In any countries, assailants and victims of the bullying of "Indirect aggression" were not stable. It was hard to premise that there were the extraordinary high-risk children with family and/or personal problems, as "Mobbning" research had done. The differences between Japan and the other four countries and the differences between Australia and the other two English-speaking countries were symbolic of the affection by the tolerance against physical violence. Japan and Australia might have less tolerate against physical violence, so their children choose the less criminal way. However, Japanese results are suggestive to other countries. Even if we reduce the usual violence and the bullying of direct aggression, we are obliged to confront the bullying of "Indirect aggression", especially social way. It is urgent for us to understand the essence of bullying correctly and to develop the intervention against it. We are required to make a new step. The restriction on usage of physical violence and weapons by laws are important. However, such interventions have no force to stop the bullying of "Indirect aggression". Especially, to stop 'excluding and ignoring', 'teasing and calling names' and 'using computer and e-mail', the proactive way should be developed but not the reactive way. We should foster "Social self efficacy (Jiko-yuyo-kan)" in the inside of children, as they do not have to keep or recover their dignity by aggrieving others. |

Bibliography

KANETSUNA, T. & SMITH, P. K., (2002). Pupil insights into bullying and coping with bullying: A bi-national study in Japan and England. Journal of School Violence, 1, 5-29.

LAGERSPETS, K. M. J., BJÖRKQVIST, K. and PELTONEN, T., (1988). Is indirect aggression typical of females? Gender differences in aggressiveness in 11 to 12-year-old children. Aggressive Behaviour, 14, 403-414.

MORITA, Y., (2001). Ijime no Kokusai Hikaku Kenkyu (in Japanese) [ International Comparative Survey on Bullying: Japan, England, Netherlands and Norway]. Tokyo: Kaneko Shobo.

National Institute for Educational Policy Research (NIER) and Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT), (2006). The Report of International Symposium on Education 2005: Save Children from the Risk of Violence in School –Based on the follow-up study and international comparison-. Tokyo: Author.

OLWEUS, D., (1993). Bullying at School: What we know and what we can do. Oxford: Blackwell Publisher Ltd.

SMITH, P. K., (1999). 'England and Wales' In P.K.Smith, Y. Morita, J. Jungar-Tas, D. Olweus, R. Catalano amd P.Slee (Eds.), The Nature of School Bullying (pp.68-90). London: Routlege.

TAKI, M., (1992). 'Ijime' Koui no Hassei Youin ni kansuru Jissyouteki Kenkyu (In Japanese) [The Empirical Study of the Occurrence of 'Ijime' Behaviour]. The Journal of Educational Sociology, 50, 366-388.

TAKI, M., (2000). Development of Bullying Prevention Programs through Mutual International Cooperation with Australia, Bulletin of the Japanese Comparative Education Society, 26, 65-75

TAKI, M., (2001). Relation among bullying, stress and stressor: A follow-up survey using panel data and a comparative survey between Japan and Australia. Japanese Society, 5, 118-133.

TAKI, M., (2003). 'Ijime bullying': Characteristics, causality and interventions . In St Catherine's College, University of Oxford, Kobe Institute (Ed.), Oxford-Kobe Seminars: Measures to Reduce "Bullying in Schools" (pp.97-113). Kobe: Editor.

LAGERSPETS, K. M. J., BJÖRKQVIST, K. and PELTONEN, T., (1988). Is indirect aggression typical of females? Gender differences in aggressiveness in 11 to 12-year-old children. Aggressive Behaviour, 14, 403-414.

MORITA, Y., (2001). Ijime no Kokusai Hikaku Kenkyu (in Japanese) [ International Comparative Survey on Bullying: Japan, England, Netherlands and Norway]. Tokyo: Kaneko Shobo.

National Institute for Educational Policy Research (NIER) and Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT), (2006). The Report of International Symposium on Education 2005: Save Children from the Risk of Violence in School –Based on the follow-up study and international comparison-. Tokyo: Author.

OLWEUS, D., (1993). Bullying at School: What we know and what we can do. Oxford: Blackwell Publisher Ltd.

SMITH, P. K., (1999). 'England and Wales' In P.K.Smith, Y. Morita, J. Jungar-Tas, D. Olweus, R. Catalano amd P.Slee (Eds.), The Nature of School Bullying (pp.68-90). London: Routlege.

TAKI, M., (1992). 'Ijime' Koui no Hassei Youin ni kansuru Jissyouteki Kenkyu (In Japanese) [The Empirical Study of the Occurrence of 'Ijime' Behaviour]. The Journal of Educational Sociology, 50, 366-388.

TAKI, M., (2000). Development of Bullying Prevention Programs through Mutual International Cooperation with Australia, Bulletin of the Japanese Comparative Education Society, 26, 65-75

TAKI, M., (2001). Relation among bullying, stress and stressor: A follow-up survey using panel data and a comparative survey between Japan and Australia. Japanese Society, 5, 118-133.

TAKI, M., (2003). 'Ijime bullying': Characteristics, causality and interventions . In St Catherine's College, University of Oxford, Kobe Institute (Ed.), Oxford-Kobe Seminars: Measures to Reduce "Bullying in Schools" (pp.97-113). Kobe: Editor.

Read also

> Summary

> 2 - Impact of school context on violence at schools

> 3 - La violence à l'école : ça vaut le coup d'agir ensemble !

> 4 - School violence in an international context : a call for global collaboration in research and prevention

> 5 - Bullying in schools: predictors and profiles. Results of the portugese health behaviour in school-aged children survey

<< Back