Article

| 4 - School violence in Spain by Rodriguez Basanta Anabel, Association Centro de Estudios de Seguridad Salarich I Banus Anna, Association Centro de Estudios de Seguridad Theme : International Journal on Violence and School, n°10, December 2009 |

| Research into violence in schools in Spain developed from the second half of the 90’s as part of a wider concern with juvenile violence. Studies on the subject progressed tentatively. Initially, the objects of the research focused on considering pupils as a threat to teachers and to their peers whereas, nowadays, the approach includes the impact made by the school and social context. Some studies focus on a reduction of violent events in school over recent years. However, there are still research subjects to explore from the criminological point of view. |

Keywords : School violence, Spain.

| PDF file here.

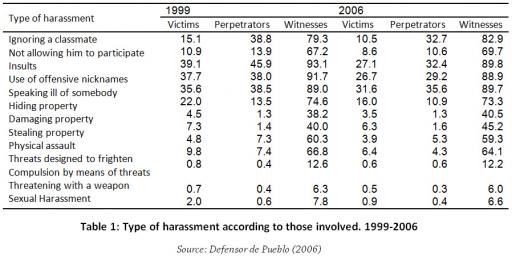

Click on the title to see the text. INTRODUCTION We have undertaken this work as part of a coordinated European action called Crimprev (Assessing Deviance, Crime and Prevention in Europe) aimed, among other aspects, at identifying factors (social, political, economic, legal, cultural) that influence the perceptions of crime and deviant behaviour and at examining crime prevention policies. More specifically, we have been entrusted with the preparation of a report on the research situation involving school violence in Spain. This work is thus divided into three main sections. - The placing of school violence in context as part of the new safety leitmotifs in Spain that we will address in section 2 of this work. - The analysis of the main lines of research on the subject (headings 3 and 4). This approach does not claim to be exhaustive. We have prioritized monographs and published reports and nationally published magazines. - The exploration of possible connections between the educational system and other systems (heading 5), considering both the possible shift of conflicts arising within the school toward action other than the intervention of external agents at the educational centre in response to these conflicts. THE EMERGENCE OF VIOLENCE AMONG YOUNG PEOPLE AS A SECURITY LEITMOTIF Recasens (2002) analyses the change in security related leitmotif in Spain during the 1980’s and 1990’s. He specifically quoted four major concerns: terrorism, immigration, drugs and juvenile delinquency. As regards this last category, between the end of the 1970’s and the start of the 1980’s, the image of juvenile insecurity concerns groups of young people living in the suburbs, affected by unemployment and the increase in the sale and consumption of heroin taking place on this time. The security problems attributed to these young people at the time are mainly connected to property crimes (vehicle thefts, muggings, etc.). In the early 1990’s, the problem of heroin-related crime decreased for a number of reasons: AIDS, the number of deaths by overdose, damage limitation and substitution (methadone) programs, juvenile court measures and social and professional integration, etc. Furthermore, the entry onto the labour market of young people from working class neighbourhoods increased at the cost, it is true, of a high level of temporary and precarious employment contracts. This economic situation has significantly reduced the presence of young offender drug addicts in the streets and in communication media. During the 1990’s, youth related security problems are based on two fundamental points. In the first place, the risks associated with the lifestyles of young people, and more particularly those related to leisure pursuits: extension of drug consumption, of reckless driving, of at risk sexual behaviour, etc . The second fundamental point is the new category of juvenile violence. Its use in our context begins with the visibility of urban tribes of juveniles and the violent acts carried out by groups of young people featuring aesthetic skinheads. The social image of skinheads was growing in turn by reason of their link to football club hooligan fans (Barruti, 1993). Young people have been the involved in other conflicts (the kaleborroka or urban violence in the Basque country, violence in schools, protests by groups of the extreme left, etc.). Widely disseminated in the media, they build a heightened and alarmist picture of juvenile violence, presenting young people as irresponsible and as a threat to the community . Thus, some research has shown the important elements of social construction involved in the definition of juvenile violence phenomena of juvenile . We do not claim to defend the existence of a simple construction of these phenomena and to deny the existence of youth-related conflicts. However, it is necessary to place the emergence of these concerns against the background of the social changes which took place in recent decades (inclusion of women in the labour market, the crisis affecting the family unit, changes to the job market structure, etc.) and which have created, particularly in the middle classes, an ontological sense of insecurity, greater tension regarding the different forms of deviance and a greater sensitivity toward the victims. As regards violence in schools, the enactment of the educational reform (from 1996 in a generalized form) provoked an increase in the tension that already existed in the school environment . As we will have the opportunity to explain below, the social communication processes associated with this reform have amplified the image of conflicts in school. From this point in time, literature on violence in schools, whether or not having an empirical basis, has increased enormously in Spain. It is possible to identify other events that will also set the pace and the direction followed by this output: - In 1998, a woman died, killed by her husband. This tragic death became the starting point for media coverage of cases of domestic violence. From this point in time, prevention plans followed each other both nationally and locally. The first programs already included lessons on non-sexist values as a fundamental element in the fight against the phenomenon. Thus, the 2004 Law on Integral Protection Measures against Domestic Violence provides for the inclusion on all school boards of a new member responsible for developing educational measures targeting equality and combating violence against women. - Educational establishments have been confronted by the challenge posed by the integration of the large contingents of immigrants who have arrived in recent years. - In September 2004, Jokin, a teenager from Hondarribia (Basque country) committed suicide after having been ill-treated for an entire year by a group of students from his school. This event attracted deep media interest. The minor's parents sued the young people involved as well as the school. The responsibilities of the educational system were undermined in the face of the emotional impact created by the facts and of the punitive reactions. This event led to an increase in scientific output and in the literature on this topic and to a proliferation of associated forums and conferences. The criminal system also reacted (Circular 10/2005 from the Public Prosecutor’s Office; reform of the Law on the Criminal Responsibility of Minors) although we question the symbolic or real significance of these measures. THE APPROACHES ON RESEARCH INTO VIOLENCE IN SCHOOLS: THE STUDENT AS A THREAT TO THE STUDY OF THE INFLUENCE OF THE SCHOOL ORGANIZATION The institutional context of education in Spain determines the absence of a national policy for the prevention of violence in schools. Thus, the State has general competences for the development of the educational system but it is the autonomous communities which are responsible for controlling and managing their own educational systems. Similarly, research projects and intervention are mainly carried out at the autonomous community or municipality level and do not develop at the same rate in the various territories. The studies into violence in schools were mainly conducted in the psycho-educational environment and have focused above all on the interpersonal conflicts between pupils although research objects have become diversified in recent years. VIOLENCE TOWARDS TEACHERS Among the first studies on conflicts and violence in educational establishments, some refer to the problems experienced by the teachers (Melero, 1993; CIDE, 1995; Buj et al., 1998). The most frequently reported conflicts involve a lack of discipline (72% of teachers quote these in the case of ICEL; 80% in the Buj study). On the other hand, aggression is not so prevalent . Despite significant efforts by the scientific community to differentiate between concepts of lack of discipline and of violence, social communication processes have submitted ambiguous data and events and have contributed to the creation of a heightened image of violence in educational establishments. In practice, in a tense situation created by the deployment of the educational reform, means of communication have reinforced the image of school-related conflict and provided important coverage for the most serious cases of violence in schools abroad. The way this information has been processed has added to the institutional actions and statements which make secondary school pupils where education was extended for two years (16 years instead of 14 years) responsible for these incidents. This diagnosis of the situation failed to take into account other structural factors of the conflict (Rodríguez, 1998) . Accordingly, the first studies on violence in schools tended to present pupils as a threat - to teachers or to their own classmates – rather than analyzing the impact of the school organization or the social context on their behaviour. INTERPERSONAL VIOLENCE BETWEEN PUPILS The first study on interpersonal violence between pupils dates of the end of the 1980s (Vieira et al., 1989 - quoted in Ortega and del Rey, 2004-. From that time, research dealing with this subject, mainly from the educational psychology point of view, has proliferated. The methodological diversity of these (mainly quantitative) studies complicates comparisons of the characteristics of violence. On the other hand, these studies are frequently carried out on small samples of institutions and do not allow results to be extrapolated to reference populations. That is why we shall wait for the next paragraph, devoted to epidemiological studies before addressing the methodological description of operations and the analysis of the impact made by the phenomenon. At this point, we shall attempt to highlight the main theoretical approaches and psycho-educational research methodologies. Most of the studies on interpersonal violence among pupils have focused on the analysis of the bullying phenomenon. The different works completed agree on the description of harassment dynamics: it is a situation involving domination or the abuse of power arising in association with various behaviour patterns (social exclusion, verbal or physical aggression, etc.) leaving the victim defenceless and in a marginalized situation. This situation is favoured by a kind of law of silence: witnesses and victims hide these facts from teachers and also, to a large extent, from parents. Almost all studies base their approach to the phenomenon on the study of aggressiveness or of antisocial conduct. Accordingly, questionnaires usually offer a list of behaviours and the category of moral harassment and the different roles involved are derived from the frequency of aggressive behaviour or exclusion. Initial studies on this subject distinguished between three types of actors: aggressors, victims and witnesses. Subsequent studies reported the existence of a fourth protagonist: the aggressive victim who suffers the most aggression and who, in turn, attacks more. Research has integrated different theoretical approaches to explain the causes and the impact of harassment: the effect of student group bonding on violence (Cerezo, 2001, 2006a, 2006b); the relationship between social contexts to explain and avoid violence (Díaz-Aguado et al., 2004); the link between moral reasoning or socio-personal values and antisocial behaviour (Díaz-Aguado et al., 2004; Ortega and del Rey, 2003, 2004; de la Fuente et al., 2006). Within the context of the analysis of psycho-social risks, works that have measured the impact of social rejection on the physical and mental health of students should also be noted (Aymerich et al. 2005; Nebot, 2006). Research has already started into the characteristics and the extent of cyber bullying (Ortega et al., 2008a). Epidemiological studies (Defensor del Pueblo, 2006; Generalitat de Catalunya, 2006) explained in the following paragraph have also included this form of harassment as one of the categories of bullying. The main objective of most of the research into violence between pupils quoted above consisted in offering harassment detection tools to teachers and educational establishments. They have also been used to establish tools for educational action . STUDIES INTO SEXIST VIOLENCE In Grañeras et al. (2007), it is possible to find a record of studies which, especially from the year 2000, analyze the social constructions and processes of socialization linked to gender based violence. Some research confirms that when the school does not encourage the formation of connections between students and social inclusion, violence, aggressiveness or the lack of discipline is involved, especially in the case of boys, in the development of a positive identity between classmates. In the case of girls, the mechanisms of the development of a social identity focus on physical considerations (Ponferrada, and Carrasco, 2008). For their part, Díaz-Aguado and Martínez (2001) have analyzed the impact of sexist values on attitudes and violent behaviour. More recently, Ortega et al. (2008b) released the results of a survey on sexual harassment between young people. INTEGRATING THE ANALYSIS OF VIOLENCE IN SCHOOLS INTO THE SCHOOL AND SOCIAL CONTEXT Psycho-educational studies undertaken on violence in schools have frequently been criticized for being too heavily based on the relationship between pupils and for ignoring the analysis of the social context of the establishments or the impact of the school organization on conflicts. However, some research has analyzed the relationship between discipline management and pupil involvement in conflicts (Del Rey and Ortega, 2005) or the climate prevailing in the establishments (Zabalza, 1999, 2002; Blaya, et al., 2006). Specifically, Del Rey and Ortega (2005) have studied the possible student perception-student opinion link with the management of discipline, its experience and its involvement in the phenomena of interpersonal violence from a survey of students in secondary education . Results show that all groups of pupils involved in violence experience more disciplinary measures (63.9% of the victims, 88.4% of aggressors and 85.4% of the aggressor/victims compared with 40.5% for those who are not involved). Thus, when reacting to those involved in the interpersonal violence, it would seem that aggressors and victims are placed at the same level. The teacher has problems in distinguishing between different roles present in the interpersonal conflict. The first study on the school climate, commissioned by the government of the Autonomous Community of Cataluna dates back to 1998 (Bisquerra and Martínez , 1998). However, attention paid to the violence was fairly circumstantial. Zabalza (1999) carried out a survey in Galicia into the connections between the entities of the education community, regulations on coexistence, conflicts and their resolution in schools; this survey was undertaken using questionnaires distributed to a sample of 907 head teachers, 836 teachers, 4,801 pupils and 3,116 parents of pupils. Educational guidance advisers were also interviewed. The results of this study reveal an essentially positive school climate. Undoubtedly the most interesting result shows that, with the exception of guidance advisers who attribute problems to the coexistence of certain teaching staff work dynamics and to the educational organization, pupils are the only ones to suggest (paying lip service) that conflicts are due to the unfair way in which they are treated when they are at the bottom academic performance scale or when they lack motivation. That is to say that the collective entities involved do not blame the organization for the conflicts created. As part of the European Observatory on violence, research was conducted in schools of the south of France and the south of Spain, applying the same methodology and the same tools to violence and to the school climate (Blaya et al., 2006) . Although the samples in this study are not representative, we wish to emphasize them in view of the comparative approach of this study. Additionally, some ethno-methodologies, although in the minority, have appeared as a very interesting tool for understanding the cultural context surrounding the creation of violence. We will be presenting some of these examples in the following paragraph. STUDIES ON IMMIGRATION AND ON SCHOOLING Since the 1990s, the integration of immigrants into schools has become the subject of routine studies. In García et al. (2008), we can find a critical review of the research conducted on this subject from the year 2000. According to the authors, many of them make the mistake of applying a view limited to a group of immigrants and schools. Notwithstanding, they recommend adopting a holistic view that positions the school, among others, in a wider socio-cultural context and which includes all young schoolchildren in the sample population in order to confirm if, in fact, there are differences due to national origins, whether or not these differences are caused by socio-economic reasons or if these differences do not exist because the problems are generated by the general way in which the educational institution is run. Studies on immigration and schooling have not focused mainly on the analysis of discrimination or violence; however, we believe that those which addressed these subjects seem remarkable because of the results produced and because they represent a good illustration of the implementation of qualitative methodologies . Serra (2002) undertook a positive investigation of the relationship between statements on the "otherness” of young people attending school and discrimination and violence. This is the secondary school ethnography of an average size city in Catalonia, having a medium-high economic level and with a significant presence of immigrants. Research shows that there are also many statements on “otherness” which is not rooted in nationalism and which define the interpersonal relations and serve to justify discriminatory and violent attitudes and behaviour. As far as the school is concerned, it develops initiatives designed to make the students think about cultural diversity but does not intervene directly in relations between students, does not work towards ending the isolation of students suffering from discrimination and towards building links between them and the rest of the pupils. Palou (2006) analysed the integration of immigrants into the school environment as part of wider ethnographic research focusing on young Latin Americans in Barcelona. The results reveals teacher ignorance on schooling conditions in the countries of origin and the cultural differences of these young people hamper integration. It also detected a tendency of teachers to attribute problems of lack of motivation and school failure to the attitude of these students. This circumstance adds to the rejection of new arrivals by native students and their families. The lack of immigrant pupil integration explains their behavioural (lack of discipline, aggressiveness) or psychological (school phobia) problems. The author emphasises this aspect by stressing that the educational programs or mechanisms designed for the purpose of integration fail to transform the system or to improve, it seems, the social integration of immigrant pupils. EPIDEMIOLOGICAL STUDIES ON BULLYING AND HARASSMENT BETWEEN PEERS Since the year 2000, many epidemiological studies designed to assess the impact of the phenomenon of harassment among peers have been carried out in Spain, both at national level in autonomous communities and in the provinces. The majority of studies analyzed aim to assess the impact of the bullying phenomenon and its different variants and modalities from the point of view of those involved (victims, aggressors and witnesses). This research reveals significant differences in the results concerning this impact because of the different methodologies used (information retrieval tools, sample characteristics, etc.) . However, some conclusions are common to all studies carried out. THE METHODOLOGICAL DIFFERENCES The majority of epidemiological studies analyzed have used quantitative techniques for collecting data, especially questionnaires for group management and for work undertaken with populations and large scale samples. The questionnaires are primarily aimed at pupils, questioned about their participation in various types of physical or psychological aggression as victim, aggressor or witness. Some studies include questionnaires aimed at teachers, seeking to obtain information on their perception of the problem of harassment between peers in their educational institution. Design and sample size As we discussed above, in most of the research work observed, the population object of study consisted of students enrolled in educational institutions. However, the curricula and the courses followed by the students can vary from one study to the other. Many studies concentrate on compulsory secondary education as in the case of the Ombudsman‘s report (Defensor del Pueblo, 2000, 2006) or the study carried out in the Reina Sofía Centre (Serrano and De, 2005). Other work focuses on the sample population of pupils attending primary or secondary education courses. That is the case of the studies undertaken by the Generalitat de Catalunya, 2006, the Government of Aragon (Gómez-Bahíllo, 2006), the La Rioja (Sáenz, 2005) or the inspectorate of the Basque Government (Oñederra, 2005a, 2005b). The size of the sample varies considerably from one study to the next. The studies with the largest samples are those of the Generalitat of Catalonia (10,414 students distributed according to their level of study: 4,951 students primary and 5,463 secondary school pupils) or that of the Government of Aragon (8,984 pupils in their final two years of primary school, secondary education, vocational education and teaching providing access to the university). The Ombudsman’s report has a sample of 3,000 pupils and the Reina Sofía Centre's study includes 800; in both cases these were secondary education pupils. The Community of Madrid Minor Ombudsman’s study also uses a large sample of 4,460 students. The sample selection is normally divided into strata that are proportional either according to gender and age variables (Reina Sofía Centre) or to areas, cycles or property in the centre (Generalitat of Catalonia, Community of Madrid Minor Ombudsman, the Community of Valencia Ombudsman) or by centres and school year (Pareja, 2002). Use made of the questionnaires The majority of surveys were performed with the use of anonymous, self-managed questionnaires targeting entire groups in the classroom, usually without the presence of a teacher. There were a few exceptions such as the computer assisted study (CATI) of the Reina Sofía Centre where the interview was carried out over the telephone. Other studies required the questionnaires to be returned by postal mail as in the case of the Government of Aragon study. Finally, we must mention the research undertaken by the Basque Government using a self-administered questionnaire completed on-line using classroom computers. INCIDENCE Bullying and harassment typology Even when studies are not directly comparable, we will give below their most important results. In almost all the studies undertaken, verbal aggression is the behaviour usually found among pupils. This is the case of the study published by the Generalitat of Catalonia (2006) which demonstrates that the incidence rate is inversely proportional to the severity of the incident. Some of the results of the study commissioned by the Community of Madrid Minor Ombudsman (Marchesi et al., 2006) confirm that verbal aggression is behaviour most frequently suffered by those who are often or always harassed (13%) followed by the physical aggression (7.7%) and social exclusion (6.6%). In the study commissioned by the Basque Government (Oñederra, 2005a, 2005b), the authors reached the conclusion that the most frequent harassment is verbal harassment and, more generally, harassment of a psychological rather than physical nature. Some studies asserted that the frequency with which a respondent states that he/she has physically attacked a fellow student exceeds the frequency of reports by victims, which could indicate that aggression is carried out in groups. This is the case of the Ombudsman’s report (2006) and of the study commissioned by the Síndic de Greuges, the Community of Valencia’s Ombudsman (Martín et al., 2006). Similarly, these studies conclude, based on pupil statements, that there are more aggressors than victims in both secondary and primary schools. Pareja (2002) stresses that the number of aggressors is higher than that of the victims even if 30.2% of the students consider that their aggression is sporadic and haphazard. All studies agree from the logical viewpoint and indicate the existence of a greater number of young schoolchildren witnesses than victims or aggressors. But here again, the most frequently occurring harassment is verbal. Some research works define an aggressor-victim category. This is the case of the Ramírez study (2006) which identifies 1% of the pupils as committing and being victims of aggression almost every day. Victim and aggressor characteristics If we allow for the gender variable of the young people involved, almost all studies confirm that more boys than girls take part in harassment (as perpetrators and as victims) with the exception of the psychological or verbal harassment categories, where girls feature more extensively (Serrano and Iborra, 2005; Defensor del Pueblo, 2006; Generalitat de Catalunya, 2006) . Pareja (2002), however, does qualify this, pointing out that the boys and girls feel ill-treated when we speak of theft or sexual harassment. Almost all of the studies report that the highest frequency of harassment occurs during the first years of study and gradually decreases over the following years. Thus, according to research carried out by Gómez-Bahíllo (2006), there is more violence in the primary schools surveyed (the last two) than in secondary schools, especially concerning physical bullying and social exclusion. Similarly, Sáenz (2005) points out that harassment in schools is more frequent in primary schools and especially among children aged 8 to 11 years (5.9%). Specifically, it is the younger children (7 and 8 year olds) who are most affected by harassment in terms of both frequency and intensity. In secondary schools, this figure drops to 2.5%. The Marchesi et al. (2006) study confirms these findings. The majority of studies analyzed offer no clear and common conclusions with regard to the ownership of institutions (public, private and under joint contract with the government) . In most of the work consulted, much of the harassment took place in the playground and in the classroom, although the different types of aggression seem to be related to a specific part of the educational establishment. Nevertheless, some studies do not concur with this assertion. The work of Martín et al. (2006) states that systematic bullying takes place in areas of the establishment where classes are not held and which are not monitored: toilets, corridors, canteen, and classrooms when the teacher is not there and at the school gates. According to the study of Oñederra (2005a, 2005b), whereas in secondary schools, the classroom is the place where attacks most usually occur according the victims (36%), the playground is where the attacks are more frequently repeated (60%) in primary schools. Another fundamental aspect considered by many research works on harassment in schools addresses cases of bullying reported by the victims. One of the conclusions reached by most of the studies analyzed is that victims tell their friends first about the abuse they suffer and then their parents but very rarely their teachers. Thus, according to Díaz-Aguado et al. (2004) from the testimonies of pupils themselves, it is not the teachers’ lack of willingness to assist the victim but rather a “he doesn’t realize” or “he can’t do anything about it” attitude. In the case of primary education, the reporting sequence is reversed: usually, the pupils tell their families, then their friends and finally the teachers. There is always a percentage of the victims, both in primary and in secondary schools, who tell nobody of their experiences. This percentage, which is important because of possible negative consequences for the victim, differs from one study to the next. THE CHANGING FACE OF HARASSMENT IN SCHOOLS There are no longitudinal studies that allow us to produce a comprehensive analysis of developments in bullying and harassment among peers. Nevertheless, we have the data from two studies, that of the Ombudsman (Defensor del Pueblo, 2000) and that of the Generalitat of Catalonia (Generalitat de Catalunya, 2001) to which a response was made in 2006. The results of the research promoted by the Ombudsman in collaboration with Unicef, reported a decrease in the incidence of different types of harassment involving the abuse of power (insults, offensive nicknames, ignoring a classmate, hiding another’s property and threats designed to frighten). Other types of harassment remain stable (indirect verbal aggression, social exclusion, the various forms of physical aggression and the most serious forms of threats). From the point of view of the attackers, the percentages of those who accept that they are the perpetrators social exclusion, insults, offensive nicknames and of those who beat and threaten others in order to scare them, have decreased. The only category which seems to have slightly increased is the one relating to thefts of property belonging to classmates. Finally, witnesses to verbal aggression are also in decline, perhaps because new forms of harassment are emerging in school (cyber bullying) which we will now discuss below. In both studies, the percentage of pupils who state that they have witnessed harassment is higher than that of victims and perpetrators. The following table details actual results by type of harassment as seen by victims, perpetrators and witnesses.

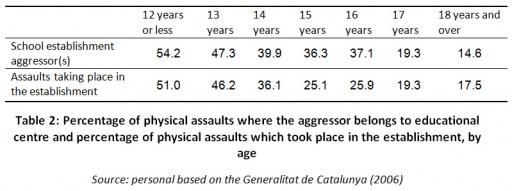

The Ombudsman’s 2006 study introduced issues relating to harassment that may have been perpetrated via new technologies (cell phones and the Internet). More specifically, 5.5% of the victims identify new technologies as a tool used to perpetrate the abuse they suffer (including 0.4% on a frequent basis). As regards the aggressors, 4.8% stated that they resort to this "sometimes" and 0.6% "very often". 22% of witnesses have observed incidents occasionally and 3% frequently. According to the authors of the report, the use of new technologies should not be considered as a new type of harassment but as a way of rendering abuse more offensive. As regards the reporting of harassment by the victims, there are large differences between the studies carried out in 2000 and those carried out 2006. In the latter study, the victims tend less to tell their friends of their experience although this remains the majority option in both studies (67.1% and 60.4% respectively). Nevertheless, the percentage of victims who report facts to teachers has increased considerably (from 8.9% to 14.2%). Another positive aspect reveals that the victims who tell nobody are on the decrease, from 16.6% to 11.2%. Finally, because of the significant increase in students of foreign origins entering the Spanish education system in recent years, it is important that we emphasize the introduction of the "national origin" variable. The Ombudsman’s report concluded that there are no significant differences in the incidence of harassment from the aggressors’ viewpoint. However, differences exist from the victims’ point of view. More specifically, the level of students who claim to be ignored is double for those of foreign extraction (20%). As regards the type of harassment where the victim is threatened with a weapon, the percentage of immigrant pupils is significantly higher than that of other students (0.4% and 1.9% respectively). It is important to emphasize that foreign students account for 7% of the total sample. The Generalitat of Catalonia in 2006 study allows us to compare the data obtained in research carried out on the 2000-2001 academic year . The comparison shows a significant increase in the perception of bullying in schools. However, cases of victims of frequent aggressive actions are declining considerably (from 13.2 to 7.8%). We may add that the number of pupils who acknowledge themselves as perpetrators of negative actions toward their classmates is also falling significantly (from 12.8% to 7.8% in the most frequent cases). This study also analyzes the influence of the "national origin" variable between the different actors involved in harassment between peers. Its conclusion is that if we consider the aggregate figures, 18.8% of young people born in Catalonia are the target of aggressive actions at least once a week whereas the percentage for young people born elsewhere rises to 23.4% (+4.6). OUTSIDE THE SCHOOL ENVIRONMENT THE SHIFT IN CONFLICTS OCCURRING OUTSIDE THE SCHOOL ENVIRONMENT The study of the Generalitat of Catalonia (2001, 2006) study also includes, among others, issues of aggressive or violent relations in all social contexts involving young people. It is important to bear in mind that the typology of victimization is changing, particularly for students of secondary school and as and when they grow older; actions become less frequent but officially more serious (Generalitat de Catalunya, 2006). Furthermore, life styles are changing and the freedom of movement of young people and the places that they go to are becoming more diverse. However, according to the same study and taking the example of physical attacks suffered by students, 40% of these acts are perpetrated by persons associated with the establishment, irrespective of the place where the aggression occurs. In the table below, we can see that assaults that took place in school decrease (by 25 points) as pupils reach the age of 16 years (usual age at which secondary schooling ends). In contrast, a strong school link persists between victims and aggressors.

We believe the studies on violence in schools should deepen the analysis of changes in forms of victimization suffered by the oldest students as well as that of its shift towards contexts other than those of the school. Until now, criminology has not investigated such issues in depth either. Thus, for example, the matter of the location of the incidents or the identity of the victims in the International Self-Report Delinquency, applied in Spain in its two editions by the Rechea team (1995, 2008) has not been analyzed. THE CRIMINAL SYSTEM AND VIOLENCE IN SCHOOLS After the Jokin case, some of the most important institutional reactions were the publication of Circular 10/2005 by the Prosecutors’ Office and the reform of the Law 5/2000 regulating the criminal liability of the Minor (LRPM). Circular 10/2005, although it recalls the subsidiary and reactive role that juvenile justice must perform, it instructs prosecutors to not to tolerate any humiliating school harassment act and to provide a response based on the law applicable to minors. It asks, for example, that action be taken in the case of behaviour that appears to be insignificant as the result of an assessment of such behaviour or that the victim is questioned whenever a complaint is made. The document also establishes the obligation of informing the educational establishment of all complaints on the subject. The LRPM reform, for its part, confirms an earlier trend where the victim was given greater importance during juvenile court cases and new preventive measures have been put in place to protect the victim. The most important, in our view, is the establishment of an injunction that can be imposed on the minor having been reported, banning him from approaching the victim or his family. Therefore, at least from a symbolic viewpoint, we see conflicts in school being externalized and moving toward the court system. Certain legal works have been published to address this judicial solution of conflicts (Rodríguez, 2006; Rodríguez, 2007; Rubio, 2007). However, there are no empirical studies analysing the extent to which the legal system in general, and the criminal justice system in particular, act as "closure clause” for the educational system. CONCLUSIONS The social and institutional concern about violence in schools arose in Spain during the second half of the 1990s within a context of the increasingly greater perception of young people as a problem and of growing tension in the education sector because of the deployment of the educational reform. There is no unanimous view on school violence within the scientific community even if research has usually adopted the issue of moral harassment (bullying) between school children as a subject for study. These works, primarily based on educational psychology, have clearly described victimization systems as well as the confusion about the roles played by victims and perpetrators. These are two issues that are frequently reported by criminology which does not, however, always analyze them empirically. The social awareness and educational programs designed to improve life within schools probably explains the development of harassment indicators (bullying) and the increased reporting of incidents by pupils as highlighted by certain recent studies. However, the results produced by research works examined recommend paying particular attention to students of immigrant origins who suffer greater victimization than their comrades. Additionally, research into this subject, like that carried out in other disciplines, such as criminology, has not yet investigated to any great depth any analysis of the changes in forms of student victimization as they grow older (the incidents decrease but tend to be more serious) or the shift of conflicts between students toward contexts other than the school environment. Finally, there is a dearth of empirical studies on the relationship between school and other actors, especially as regards the trend towards legal settlement of conflicts or interaction with the officers of the criminal system. In practice, there are many examples of collaboration between such institutions, but we cannot say whether or not their roles have changed. |

Bibliography

AYMERICH M., BERRA S., GUILLAMON I., HERDMAN M., ALONSO J., RAVENS-SIEBERER U., RAJMIL L., (2005), Desarrollo de la versión en español del KIDSCREEN, un cuestionario de calidad de vida para la población infantil y adolescente, Gaceta Sanitaria, 19, 2, 93-102, http://external.doyma.es/pdf/138/138v19n02a13074364pdf001.pdf

BARRUTI M., DÍAZ A., ROMANÍ O., (1993), El món dels joves a Barcelona. Imatges I estils juvenils, Barcelone, Ajuntament de Barcelona.

BIQUERRA R., MARTINEZ M., (1998), El clima escolar als centres d´Ensenyament Secundari a Catalunya, Barcelone, Departament d´Ensenyament, Generalitat de Catalunya.

BLAYA C., DEBARBIEUX E., DEL REY R., ORTEGA R., (2006), Clima y violencia escolar. Un estudio comparativo entre España y Francia, Revista de Educación, 339, 293-315, http://www.revistaeducacion.mec.es/re339/re339_13.pdf

BUJ A. et al., (1998), Funcionamiento de los centros. Diagnóstico del Sistema Educativo. 1997, Madrid, Ministerio de Educación y Cultura.

CEREZO F., (2001), La violencia en las aulas. Análisis y propuestas de intervención, Madrid, Pirámide.

CEREZO F., (2006a), Violencia y victimización entre escolares. El bullying: estrategias de identificación y elementos para la intervención a través del Test Bull-S, Revista Electrónica de Investigación Psicoeducativa, 9, 4, 2, 333-352.

CEREZO F., (2006b), Análisis comparativo de variables socio-afectivas diferenciales entre los implicados en el bulling. Estudio de un caso de víctima provocador, Anuario de Psicología Clínica y de Salud, 2, 27-34.

CIDE, (1995), Evaluación del profesorado de educación secundaria. Análisis de tendencias y diseño de un plan de evaluación, Madrid, Ministerio de Educación y Ciencia.

COMAS D., (2003), Jóvenes y estilos de vida: valores y riesgos en los jóvenes urbanos, Madrid, Injuve-FAD.

DE LA FUENTE J., PERALTA F.J., SÁNCHEZ M.D., (2006), Valores sociopersonales y problemas de convivencia en la Educación Secundaria, Revista Electrónica de Investigación Psicoeducativa, 9, 4, 2, 171-200,

http://www.investigacion-psicopedagogica.org/revista/articulos/9/espannol/Art_9_118.pdf

DEBARBIEUX E., (Ed.), (1996), La violence en milieu scolaire. 1: Etat des lieux, Paris, ESF.

DEFENSOR DEL PUEBLO, (2000), Violencia escolar: el maltrato entre iguales en la educación secundaria obligatoria, Madrid, Defensor del Pueblo. (Direction de la recherche : Del Barrio C., Martín E.).

DEFENSOR DEL PUEBLO, (2006), Informe del Defensor del Pueblo sobre violencia escolar: el maltrato entre iguales en la Educación Secundaria Obligatoria, Madrid, Defensor de Pueblo (Direction de la recherche : Del Barrio C., Espinosa MA., Martín E., Ochaíta E.)

DEL REY R., ORTEGA R., (2005), Violencia interpersonal y gestión de la disciplina. Un estudio preliminar, Revista Mexicana de Investigación Educativa, 10, 026, 805-832, http://redalyc.uaemex.mx/redalyc/pdf/140/14002610.pdf

DIAZ-AGUADO M.J, (2004a), Prevención de la violencia entre iguales en la escuela y en el ocio. Programa de intervención y estudio experimental, 2, Madrid, Injuve.

DIAZ-AGUADO M.J, (2004b), Prevención de la violencia y lucha contra la exclusión social en la adolescencia. Intervención a través de la familia, 3, Madrid, Injuve.

DÍAZ-AGUADO M.J., MARTÍNEZ R., (2001), La construcción de la Igualdad y la prevención de la violencia contra la mujer desde la educación secundaria, Madrid, Instituto de la Mujer, Ministerio de Trabajo y Asuntos sociales.

DIAZ-AGUADO M.J., MARTINEZ R., MARTIN G., (2004), La violencia entre iguales en la escuela y en el ocio. Estudios comparativos e instrumentos de evaluación, 1, Madrid, Injuve.

ELZO J., (Ed.), (1996), Drogas y escuela V, Bilbao, Gobierno Vasco.

ELZO J., (1999), Jóvenes en crisis. Aspectos de jóvenes violentos. Violencia y drogas, in Rechea C., Ed., La criminología aplicada II, Cuadernos de derecho judicial, Madrid, Consejo General del Poder Judicial.

FEIXA C., (1998), De jóvenes, bandas y tribus, Barcelone, Ariel.

FEIXA C,. (Ed.), (2006), Jóvenes 'latinos' en Barcelona. Espacio público y cultura urbana, Barcelone, Anthropos-Ajuntament de Barcelona

GARCIA F.J., RUBIO M., BOUACHRA O., (2008), Población inmigrante y escuela en España: un balance de investigación, Revista de Educación, 34, 23-60, http://www.revistaeducacion.mec.es/re345/re345_02.pdf

GENERALITAT DE CATALUNYA, (2001), Joventut i Seguretat a Catalunya. Enquesta als joves escolaritzats de 12 a 18 anys, Barcelone, Departament d'Educació i Departament d'Interior, Generalitat de Catalunya.

GENERALITAT DE CATALUNYA, (2006), Enquesta de convivència escolar i seguretat a Catalunya. Barcelone, Departament d'Educació i Departament d'Interior, Generalitat de Catalunya.

GOMEZ-BAHILLO C. (Ed.), (2006), Las relaciones de convivencia y conflicto escolar en los centros educativos aragoneses de enseñanza no universitaria, Saragosse, Gobierno de Aragón, http://www.educa.aragob.es/ryc/Convi.es/Descargas/INFORME por10020PRELIMINAR.pdf

GRAÑERAS M., MAÑERU A., MARTIN R., DE LA TORRE C., ALCALDE A., (2007), La prevención de la violencia contra las mujeres desde la educación: investigaciones y actuaciones educativas públicas y privadas, Revista de Educación, 342, 189-209, http://www.revistaeducacion.mec.es/re342/re342_10.pdf

MARCHESI A., MARTIN E., PEREZ E. M., DIAZ T., (2006), Convivencia, conflictos y educación en los centros escolares de la Comunidad de Madrid, Madrid, Defensor del Menor de la Comunidad de Madrid.

MARTÍN A., MARTÍNEZ JM., LÓPEZ JS., MARTÍN MJ., MARTÍN JM., (1997), Comportamientos de riesgo: violencia, prácticas sexuales de riesgo y consumo de drogas ilegales en la juventud, Madrid, Entinema.

MARTIN E., PEREZ F., MARCHESI A., PEREZ E. M., ÁLVAREZ N., (2006), Estudio Epidemiológico del Bullying en la Comunitat Valenciana, Valence, Síndic de Greuges de la Comunitat Valenciana.

MEGÍAS E., (Ed.) , (2001), Valores sociales y drogas, Madrid, FAD.

MELERO J., (1993), Conflictividad y violencia en los centros escolares, Mexique-Espgane, Siglo XXI Editores.

NEBOT M., (2006), Factors de risc en estudiants de secundaria de Barcelona. Resultats principals de l'informe FRESC. 2004, Barcelone, Agència de Salut pública de Barcelona, http://www.aspb.es/quefem/docs/informe_fresc_2004.pdf

OÑEDERRA J.A. et al., (2005a), El maltrato entre iguales, Bullying en Euskadi. Educación Primaria, Vitoria-Gasteiz, Gobierno Vasco, ISEIIVEI, http://www.isei-ivei.net

OÑEDERRA J.A. et al., (2005b), El maltrato entre iguales, Bullying en Euskadi. Educación Secundaria, Vitoria-Gasteiz, Gobierno Vasco, ISEIIVEI, http://www.isei-ivei.net

ORTEGA R., (1994), Violencia interpersonal en los centros de Eduación Secundaria. Un estudio sobre maltrato e intimidación entre compañeros, Revista de Eduación, 304, 253-280.

ORTEGA R., (1997), El proyecto Sevilla antiviolencia escolar. Un modelo de intervención preventiva contra los malos tratos entre iguales, Revista de Educación, 313, 143-158.

ORTEGA R., MORA-MERCHAN J. A., (2000), Violencia escolar. Mito o realidad, Séville, Mergablum.

ORTEGA R., DEL REY R., (2003), La violencia escolar. Estrategias de prevención, Barcelone, Graó.

ORTEGA R., DEL REY R., (2004), Construir la convivencia, Barcelone, Edebé.

ORTEGA R.; CALMAESTRA J., MORA-MERCHAN J., (2008a), Cyberbullying, International Journal of Psychology and Psychological Therapy, 8, 2, 183-192.

ORTEGA R., ORTEGA F.J., SANCHEZ V., (2008b), Sexual harassment among peers and adolescent dating violence, International Journal of Psychology and Psychological Therapy, 8, 1, 63-72, http://www.ijpsy.com/

PALOU M., (2006), Jóvenes 'latinos' y medio escolar, in FEIXA D., Ed., Jóvenes 'latinos' en Barcelona. Espacio público y cultura urbana, Barcelone, Anthropos-Ajuntament de Barcelona, 223-246.

PAREJA A., (2002), La violencia escolar en contextos interculturales. Un estudio de la Ciudad Autónoma de Ceuta, Thèse de doctorat, Université de Grenade.

PONFERRADA M., CARRASCO S., (2008), Climas escolares, malestares y relaciones entre iguales en las escuelas catalanas de secundaria, Revista d'estudis de la violència, 4, 1-21, http://www.icev.cat/articulo_bullying_UAB.pdf.

RAMIREZ S., (2006), El maltrato entre escolares y otras conductas-problemas para la convivencia: Un estudio desde el contexto del grupo-clase, Thèse de doctorat, Université de Grenade.

RECASENS A., (2002), Security and Crime Prevention Policies in Spain in the 1990's, in Hebberercht P., Duprez D., (Eds.), The Prevention and Security Policies in Europe, Brussels, Vubpress, 209-236.

RECHEA C., (2008), Conductas antisociales y delictivas de los jóvenes en España, Consejo General del Poder Judicial-Centro de Investigación en Criminología, http://www.uclm.es/criminologia/pdf/16_2008.pdf

RECHEA C., BARBERET R., MONTAÑÉS J., ARROYO L., (1995) La Delincuencia Juvenil en España: Autoinforme de los Jóvenes, Madrid, Ministerio de Justicia e Interior.

RODRIGUEZ A., (1998), Estudi exploratori sobre la informació relativa a la violència escolar a Catalunya (1996-1998), rapport de recherche, Mollet del Vallès, Escola de Policia de Catalunya.

RODRIGUEZ P., (2006), Acoso escolar. Desde el mal llamado bullying hasta el acoso al profesorado (Especial análisis de la reparación del daño), Barcelone, Atelier.

RODRIGUEZ C., (2007), La responsabilidad civil del bullying y otros delitos de los menores de edad, Madrid, Laberinto Jurídico.

RUBIO P.A., (2007), Violencia en los centros escolares y derecho penal, Madrid, CESEJ.

SABATE J., ARAGAY J.M., TORRELLES, E., (2000), 1999: La delinqüència a l’Àrea Metropolitana de Barcelona. 11 anys d’enquestes de victimització, Barcelone, Institut d’Estudis Metropolitans de Barcelona.

SAENZ T. et al., (2005), El acoso escolar en los centros educativos de La Rioja, La Rioja, Servicio de Inspección Técnica Educativa, Sector Rioja Baja-Logroño Este.

SERRA C., (2002), Identitat, racisme i violència. Les relacions interètniques en un institut català, thèse de doctorat, Université de Girone.

SERRA C., (2004), Etnografía escolar, etnografía de la educación, Revista de Educación, 334, 165-176.

SERRANO A., IBORRA I., (2005), Violencia entre compañeros en la escuela, Valence, Centro Reina Sofía para el Estudio de la Violencia.

ZABALZA M.A., (Ed.), (1999), A convivencia nos centros escolares de Galicia, Saint-Jacques-de-Compostelle, Consellería de Educación e Ordenación Universitaria.

ZABALZA M.A., (2002), Situación de la convivencia escolar en España: Políticas de intervención, Revista ínteruniversitaria de formación del profesorado, 44, 139-174, http://redalyc.uaemex.mx/redalyc/src/inicio/ArtPdfRed.jsp?iCve=27404408

BARRUTI M., DÍAZ A., ROMANÍ O., (1993), El món dels joves a Barcelona. Imatges I estils juvenils, Barcelone, Ajuntament de Barcelona.

BIQUERRA R., MARTINEZ M., (1998), El clima escolar als centres d´Ensenyament Secundari a Catalunya, Barcelone, Departament d´Ensenyament, Generalitat de Catalunya.

BLAYA C., DEBARBIEUX E., DEL REY R., ORTEGA R., (2006), Clima y violencia escolar. Un estudio comparativo entre España y Francia, Revista de Educación, 339, 293-315, http://www.revistaeducacion.mec.es/re339/re339_13.pdf

BUJ A. et al., (1998), Funcionamiento de los centros. Diagnóstico del Sistema Educativo. 1997, Madrid, Ministerio de Educación y Cultura.

CEREZO F., (2001), La violencia en las aulas. Análisis y propuestas de intervención, Madrid, Pirámide.

CEREZO F., (2006a), Violencia y victimización entre escolares. El bullying: estrategias de identificación y elementos para la intervención a través del Test Bull-S, Revista Electrónica de Investigación Psicoeducativa, 9, 4, 2, 333-352.

CEREZO F., (2006b), Análisis comparativo de variables socio-afectivas diferenciales entre los implicados en el bulling. Estudio de un caso de víctima provocador, Anuario de Psicología Clínica y de Salud, 2, 27-34.

CIDE, (1995), Evaluación del profesorado de educación secundaria. Análisis de tendencias y diseño de un plan de evaluación, Madrid, Ministerio de Educación y Ciencia.

COMAS D., (2003), Jóvenes y estilos de vida: valores y riesgos en los jóvenes urbanos, Madrid, Injuve-FAD.

DE LA FUENTE J., PERALTA F.J., SÁNCHEZ M.D., (2006), Valores sociopersonales y problemas de convivencia en la Educación Secundaria, Revista Electrónica de Investigación Psicoeducativa, 9, 4, 2, 171-200,

http://www.investigacion-psicopedagogica.org/revista/articulos/9/espannol/Art_9_118.pdf

DEBARBIEUX E., (Ed.), (1996), La violence en milieu scolaire. 1: Etat des lieux, Paris, ESF.

DEFENSOR DEL PUEBLO, (2000), Violencia escolar: el maltrato entre iguales en la educación secundaria obligatoria, Madrid, Defensor del Pueblo. (Direction de la recherche : Del Barrio C., Martín E.).

DEFENSOR DEL PUEBLO, (2006), Informe del Defensor del Pueblo sobre violencia escolar: el maltrato entre iguales en la Educación Secundaria Obligatoria, Madrid, Defensor de Pueblo (Direction de la recherche : Del Barrio C., Espinosa MA., Martín E., Ochaíta E.)

DEL REY R., ORTEGA R., (2005), Violencia interpersonal y gestión de la disciplina. Un estudio preliminar, Revista Mexicana de Investigación Educativa, 10, 026, 805-832, http://redalyc.uaemex.mx/redalyc/pdf/140/14002610.pdf

DIAZ-AGUADO M.J, (2004a), Prevención de la violencia entre iguales en la escuela y en el ocio. Programa de intervención y estudio experimental, 2, Madrid, Injuve.

DIAZ-AGUADO M.J, (2004b), Prevención de la violencia y lucha contra la exclusión social en la adolescencia. Intervención a través de la familia, 3, Madrid, Injuve.

DÍAZ-AGUADO M.J., MARTÍNEZ R., (2001), La construcción de la Igualdad y la prevención de la violencia contra la mujer desde la educación secundaria, Madrid, Instituto de la Mujer, Ministerio de Trabajo y Asuntos sociales.

DIAZ-AGUADO M.J., MARTINEZ R., MARTIN G., (2004), La violencia entre iguales en la escuela y en el ocio. Estudios comparativos e instrumentos de evaluación, 1, Madrid, Injuve.

ELZO J., (Ed.), (1996), Drogas y escuela V, Bilbao, Gobierno Vasco.

ELZO J., (1999), Jóvenes en crisis. Aspectos de jóvenes violentos. Violencia y drogas, in Rechea C., Ed., La criminología aplicada II, Cuadernos de derecho judicial, Madrid, Consejo General del Poder Judicial.

FEIXA C., (1998), De jóvenes, bandas y tribus, Barcelone, Ariel.

FEIXA C,. (Ed.), (2006), Jóvenes 'latinos' en Barcelona. Espacio público y cultura urbana, Barcelone, Anthropos-Ajuntament de Barcelona

GARCIA F.J., RUBIO M., BOUACHRA O., (2008), Población inmigrante y escuela en España: un balance de investigación, Revista de Educación, 34, 23-60, http://www.revistaeducacion.mec.es/re345/re345_02.pdf

GENERALITAT DE CATALUNYA, (2001), Joventut i Seguretat a Catalunya. Enquesta als joves escolaritzats de 12 a 18 anys, Barcelone, Departament d'Educació i Departament d'Interior, Generalitat de Catalunya.

GENERALITAT DE CATALUNYA, (2006), Enquesta de convivència escolar i seguretat a Catalunya. Barcelone, Departament d'Educació i Departament d'Interior, Generalitat de Catalunya.

GOMEZ-BAHILLO C. (Ed.), (2006), Las relaciones de convivencia y conflicto escolar en los centros educativos aragoneses de enseñanza no universitaria, Saragosse, Gobierno de Aragón, http://www.educa.aragob.es/ryc/Convi.es/Descargas/INFORME por10020PRELIMINAR.pdf

GRAÑERAS M., MAÑERU A., MARTIN R., DE LA TORRE C., ALCALDE A., (2007), La prevención de la violencia contra las mujeres desde la educación: investigaciones y actuaciones educativas públicas y privadas, Revista de Educación, 342, 189-209, http://www.revistaeducacion.mec.es/re342/re342_10.pdf

MARCHESI A., MARTIN E., PEREZ E. M., DIAZ T., (2006), Convivencia, conflictos y educación en los centros escolares de la Comunidad de Madrid, Madrid, Defensor del Menor de la Comunidad de Madrid.

MARTÍN A., MARTÍNEZ JM., LÓPEZ JS., MARTÍN MJ., MARTÍN JM., (1997), Comportamientos de riesgo: violencia, prácticas sexuales de riesgo y consumo de drogas ilegales en la juventud, Madrid, Entinema.

MARTIN E., PEREZ F., MARCHESI A., PEREZ E. M., ÁLVAREZ N., (2006), Estudio Epidemiológico del Bullying en la Comunitat Valenciana, Valence, Síndic de Greuges de la Comunitat Valenciana.

MEGÍAS E., (Ed.) , (2001), Valores sociales y drogas, Madrid, FAD.

MELERO J., (1993), Conflictividad y violencia en los centros escolares, Mexique-Espgane, Siglo XXI Editores.

NEBOT M., (2006), Factors de risc en estudiants de secundaria de Barcelona. Resultats principals de l'informe FRESC. 2004, Barcelone, Agència de Salut pública de Barcelona, http://www.aspb.es/quefem/docs/informe_fresc_2004.pdf

OÑEDERRA J.A. et al., (2005a), El maltrato entre iguales, Bullying en Euskadi. Educación Primaria, Vitoria-Gasteiz, Gobierno Vasco, ISEIIVEI, http://www.isei-ivei.net

OÑEDERRA J.A. et al., (2005b), El maltrato entre iguales, Bullying en Euskadi. Educación Secundaria, Vitoria-Gasteiz, Gobierno Vasco, ISEIIVEI, http://www.isei-ivei.net

ORTEGA R., (1994), Violencia interpersonal en los centros de Eduación Secundaria. Un estudio sobre maltrato e intimidación entre compañeros, Revista de Eduación, 304, 253-280.

ORTEGA R., (1997), El proyecto Sevilla antiviolencia escolar. Un modelo de intervención preventiva contra los malos tratos entre iguales, Revista de Educación, 313, 143-158.

ORTEGA R., MORA-MERCHAN J. A., (2000), Violencia escolar. Mito o realidad, Séville, Mergablum.

ORTEGA R., DEL REY R., (2003), La violencia escolar. Estrategias de prevención, Barcelone, Graó.

ORTEGA R., DEL REY R., (2004), Construir la convivencia, Barcelone, Edebé.

ORTEGA R.; CALMAESTRA J., MORA-MERCHAN J., (2008a), Cyberbullying, International Journal of Psychology and Psychological Therapy, 8, 2, 183-192.

ORTEGA R., ORTEGA F.J., SANCHEZ V., (2008b), Sexual harassment among peers and adolescent dating violence, International Journal of Psychology and Psychological Therapy, 8, 1, 63-72, http://www.ijpsy.com/

PALOU M., (2006), Jóvenes 'latinos' y medio escolar, in FEIXA D., Ed., Jóvenes 'latinos' en Barcelona. Espacio público y cultura urbana, Barcelone, Anthropos-Ajuntament de Barcelona, 223-246.

PAREJA A., (2002), La violencia escolar en contextos interculturales. Un estudio de la Ciudad Autónoma de Ceuta, Thèse de doctorat, Université de Grenade.

PONFERRADA M., CARRASCO S., (2008), Climas escolares, malestares y relaciones entre iguales en las escuelas catalanas de secundaria, Revista d'estudis de la violència, 4, 1-21, http://www.icev.cat/articulo_bullying_UAB.pdf.

RAMIREZ S., (2006), El maltrato entre escolares y otras conductas-problemas para la convivencia: Un estudio desde el contexto del grupo-clase, Thèse de doctorat, Université de Grenade.

RECASENS A., (2002), Security and Crime Prevention Policies in Spain in the 1990's, in Hebberercht P., Duprez D., (Eds.), The Prevention and Security Policies in Europe, Brussels, Vubpress, 209-236.

RECHEA C., (2008), Conductas antisociales y delictivas de los jóvenes en España, Consejo General del Poder Judicial-Centro de Investigación en Criminología, http://www.uclm.es/criminologia/pdf/16_2008.pdf

RECHEA C., BARBERET R., MONTAÑÉS J., ARROYO L., (1995) La Delincuencia Juvenil en España: Autoinforme de los Jóvenes, Madrid, Ministerio de Justicia e Interior.

RODRIGUEZ A., (1998), Estudi exploratori sobre la informació relativa a la violència escolar a Catalunya (1996-1998), rapport de recherche, Mollet del Vallès, Escola de Policia de Catalunya.

RODRIGUEZ P., (2006), Acoso escolar. Desde el mal llamado bullying hasta el acoso al profesorado (Especial análisis de la reparación del daño), Barcelone, Atelier.

RODRIGUEZ C., (2007), La responsabilidad civil del bullying y otros delitos de los menores de edad, Madrid, Laberinto Jurídico.

RUBIO P.A., (2007), Violencia en los centros escolares y derecho penal, Madrid, CESEJ.

SABATE J., ARAGAY J.M., TORRELLES, E., (2000), 1999: La delinqüència a l’Àrea Metropolitana de Barcelona. 11 anys d’enquestes de victimització, Barcelone, Institut d’Estudis Metropolitans de Barcelona.

SAENZ T. et al., (2005), El acoso escolar en los centros educativos de La Rioja, La Rioja, Servicio de Inspección Técnica Educativa, Sector Rioja Baja-Logroño Este.

SERRA C., (2002), Identitat, racisme i violència. Les relacions interètniques en un institut català, thèse de doctorat, Université de Girone.

SERRA C., (2004), Etnografía escolar, etnografía de la educación, Revista de Educación, 334, 165-176.

SERRANO A., IBORRA I., (2005), Violencia entre compañeros en la escuela, Valence, Centro Reina Sofía para el Estudio de la Violencia.

ZABALZA M.A., (Ed.), (1999), A convivencia nos centros escolares de Galicia, Saint-Jacques-de-Compostelle, Consellería de Educación e Ordenación Universitaria.

ZABALZA M.A., (2002), Situación de la convivencia escolar en España: Políticas de intervención, Revista ínteruniversitaria de formación del profesorado, 44, 139-174, http://redalyc.uaemex.mx/redalyc/src/inicio/ArtPdfRed.jsp?iCve=27404408

Read also

> Summary

> 1 - Problem behaviour and prevention

> 2 - Schools being tested by violence

> 3 - Deviant behaviour and violence in Luxembourg schools

> 5 - European trends in research into violence and deviance in schools

> 6 - Extra - Stakes of violence in education in Africa

<< Back